Ski tracks traversing toward a slide path below the "Widow Maker" on Mt. Herman. Lee Lazzara photo courtesy of Northwest Avalanche Center.

Ski tracks traversing toward a slide path below the "Widow Maker" on Mt. Herman. Lee Lazzara photo courtesy of Northwest Avalanche Center.By John Minier

The rain began on Thursday, January 21. Over the next 48 hours, the Mt. Baker Heather Meadows weather station recorded 7 inches of water. The rain worked its way down through the snow, breaking bonds between the grains.

In some areas, the weight of all the rain was too much; slopes failed and avalanched into the valleys below. Despite the natural avalanche cycle, layers of snow on the steep north face of Mt. Herman groaned and shifted, but did not slide.

By Saturday, temperatures were cooling again. A weak weather system brushed the area on Saturday night and on Sunday the skies began to clear. Fresh snow sat lightly on the surface, beckoning to backcountry skiers and snowboarders. As the day wore on, the snow along the north face of Mt. Herman continued to settle and shift. Finally, in the early afternoon, gravity won. The entire snowpack released its grip on the steep, rocky slabs to which it clung. Directly below, two men were desperately fighting for their lives.

Broken memories

I met Peter in late summer. He was chatting casually with Frank, the boot fitter at Backcountry Essentials known for his conversational skills. I walked past the two of them and into my office. Frank followed me in, closed the door and said, “There’s somebody I think you should speak with. He was involved in the avalanche accident at Baker last season.”

Peter and I sat and talked for a half hour. It seemed like his first opportunity to discuss the accident with someone in the ski and avalanche industry. He had many questions regarding the avalanche and I answered them as best I could, based on the information in the official accident report produced by the Northwest Avalanche Center (NWAC). Dissecting the events of the accident is nearly impossible due to Peter’s complete loss of memory of the incident. He suffered a serious head injury at some point during the avalanche and has no recollection of anything from about one month prior to the accident until three weeks after.

Peter didn’t learn that Mark, his friend and ski partner that day, had died until well after the fact. It wasn’t an easy lesson. Throughout his early recovery, Peter had a hard time turning short-term memories into long-term ones. “I had to be told like four or five times. I had the same reaction every time,” he said.

I met up with Peter again this fall to chat in a more private setting. The conversation was a little more personal, and we spoke about his relationship with Mark. “He was just such a nice dude. You know, you get that feeling about people.” Their flexible schedules made them the perfect backcountry partners. “It was bad. Both of us were very easily convinced to not work,” he said.

Despite only having known each other since the previous summer, Peter and Mark managed to do quite a bit of skiing. “That was number 32,” Peter said, when asked how many days he had skied before the accident. “And maybe number 15 with Mark. We both really loved skiing.”

“I kind of got to know his family. He has two kids,” Peter said. “He had been skiing the Cascades for quite a long time. He wasn’t the type to take risks. I like that. I really appreciated that. More than half the time when we were skiing, we would actually dig a pit and check the snowpack – actually do the shit that we had learned.”

Peter wore a GoPro on the day of his accident. The limited footage provides the only clues as to what happened. At some point Peter fell and was injured. Around 12:40 p.m., Mark called 911 to request assistance. Bellingham Mountain Rescue and the Mt. Baker Ski Patrol spotted the two from the Heather Meadows parking lot and made contact with a megaphone. Peter had suffered a head and leg injury, and was sliding slowly downhill with Mark’s assistance. Above the two men loomed the steep north face of Mt. Herman, a feature commonly called the “Widow Maker.”

Underlying problems

As an avalanche educator, much of what I do is distill a complex phenomenon down into its basic concepts. There is, however, a limit to how much we can simplify avalanche hazard.

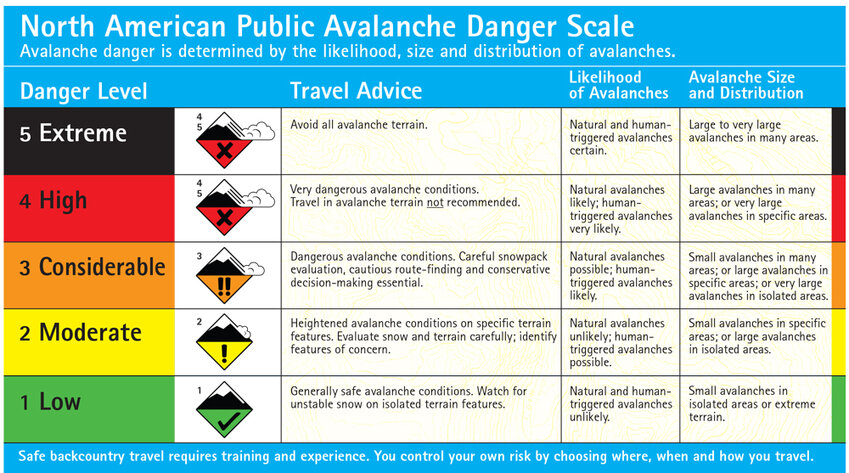

When I spoke to Peter about the avalanche hazard at the time of the accident, he said, “The day that we got into trouble was a two. I based a lot of decisions on that number. I’ve done twos. Tons of them.” Every day throughout the winter, NWAC publishes a current avalanche forecast on nwac.us. The forecast includes a numerical rating of the anticipated avalanche hazard. The number 2 refers to “moderate” hazard on the North American Public Avalanche Danger Scale. The scale ranges from 1 to 5, or low to extreme. Each hazard level is defined by the probability of an avalanche occurring, as well as the size and distribution of expected avalanches. The hazard rating provides a lot of information, but doesn’t give a complete picture.

You must also know which avalanche problems are present. Fortunately, avalanche forecasters will list out all the different types of problems along with the hazard rating. Different avalanche problems can occur in different places in terrain, and need to be managed very differently. As backcountry travelers, we don’t build experience with avalanche hazard as much as we build experience with avalanche problems. If you commonly ski or ride the Mt. Baker backcountry, you’re probably used to dealing with storm slab and wind slab, but that doesn’t mean you know the first thing about managing problems less common to the area.

Mark and Peter were caught by a glide avalanche that released naturally above them. Glide avalanches occur when water lubricates the snow-ground interface and the entire snowpack releases suddenly. The glide avalanche in the Widow Maker was most likely an isolated avalanche problem, which suggests that it didn’t exist throughout the terrain. Isolated avalanche problems are difficult, but not impossible, to predict.

It’s important to note that Mark and Peter did not trigger the glide avalanche, but they were in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Backcountry bullfighting

My conversations with Peter got me thinking about operational decision-making in avalanche terrain. I own Mt. Baker Mountain Guides with my wife Jenni, and we cater to many clients who come to Mt. Baker to backcountry ski and snowboard, or take one of our avalanche courses. We put a lot of people into avalanche terrain all winter long, year after year.

Our decision-making process begins before entering the field. At Mt. Baker Mountain Guides, we have designed a proprietary morning form that serves as a pre-trip checklist. The purpose of our morning form is to get our guides thinking critically about hazard, and assist them in identifying concerns that may or may not be included in the NWAC avalanche forecast. On the day of Mark and Peter’s accident, NWAC didn’t list glide avalanches as a problem. However, careful assessment of the conditions both before and during the event could have indicated a glide avalanche concern in terrain such as the Widow Maker.

The whole point of completing a morning form is to relate avalanche hazard to terrain, and identify areas to avoid. Another tool that we use is a run list. Run lists include maps, photos, satellite imagery and other resources used to identify avalanche terrain. Common runs are drawn in and named. Before a day of touring, we sit down and rate each run as either open or closed based on the avalanche forecast and our morning form. Open runs can be considered as options once we’re in the field, but can also be closed at the discretion of the guide. Closed runs can never be opened. All runs must be rated, and ratings are to be respected. Those are the rules and we follow them religiously.

Run lists are just one technique we use to limit emotion in the decision-making process. Practically any decisions that we make in the field will have an emotional component, so we make as many as we can before we put our skins on.

The problem with emotions is that they can get us into serious trouble. The avalanche phenomenon is mind boggling in its complexity. As humans, we work best when we break complex problems down into manageable pieces and deal with each individually. If we fail to do so, our brains will shortcut the process for us, sometimes with tragic consequences. These shortcuts are known as heuristics, or human factors, and they’re wide-ranging. Here’s one example: “I’ve skied this run 20 times, and I’ve never seen it slide!” Human factors are very difficult to predict and common in nearly all avalanche accidents. We try to solve them with good communication, checklists, rules, and other decision-making frameworks, but we are still human. The best we can do is stack the deck in our favor.

The point is that if your decision-making is entirely premised on a number between one and five, you’re eventually going to get burned. There are simply too many factors to consider. Backcountry travel is a numbers game. If you plan on skiing or riding 1,000 days over the course of your life, and you’re wrong 1 percent of the time, you could die 10 times.

If you expect to play the game for any length of time, you must be willing to approach it with a professional mindset. In many ways, there is no such thing as a recreational backcountry skier or snowboarder. It’s like saying you’re a recreational bullfighter.

Creating tomorrow

In the time I spent with Peter, he talked a little about staying positive and moving forward. “My wife got an internship at the hospital that I was at,” he said. “I keep looking for those silver linings.”

Peter plans to continue his avalanche education with an AIARE Level 3 avalanche course. When he initially asked my opinion regarding the AIARE Level 3, I told him that it was an operational decision-making course designed for professionals. Peter has plans to make a full return to skiing and his passion for the backcountry is palpable. The AIARE Level 3 may be exactly what he needs.

All backcountry skiers and snowboarders can benefit from continuing education. However, there is much you can do outside of the classroom. If you don’t have any avalanche education, take a course.

If you do, practice what you learned. Buy an AIARE field book, and use the pre-trip checklist and other provided tools to assess avalanche hazard. Write it down. Relate the hazard

to terrain. Fall Line Publishing has produced a Mt. Baker Backcountry Ski Map that doubles as a run list. Run lists are great because they don’t pigeonhole you into a specific objective, but they help you avoid dangerous terrain and control your emotions.

Most importantly, find partners who value your approach and want to learn with you. These are people who you are literally trusting with your life, and it’s been proven that small group decision-making is superior. You’ll most likely plan better tours and ski better snow, but the best part is coming home at the end of the day. x

John Minier is the owner and lead guide of Mt. Baker Mountain Guides. Originally from Alaska, he has a deep appreciation and respect for wild and mountainous places.