By Jason Griffith

The long days of sweating up trails and swatting flies are mostly behind us. Fortunately, the cool, crisp days of fall are a wonderful time in the high alpine of the Cascades. Many consider fall the best season for hiking, and for good reason. The bright scarlet of huckleberry foliage and the vine maple’s intense orange can rival New England for calendar-worthy fall scenes, especially with a dash of early snow.

But the colors of alpine larch trees steal the show in early October, when their needles turn gold before falling off in the wind. Larch glades provide a color diorama that one can actually walk within, completely surrounded by dazzling gold.

The beauty of an alpine larch grove in peak fall color is limited in both time and space and that’s part of the draw. The rest of the year the trees are hidden in plain sight, their green needles blending in with subalpine fir and other conifers. Figuring out where and when to find larches in their full glory presents a challenge to hikers, but knowing their fascinating life history can allow one to get away from the weekend crowds and the more popular larch hikes (see examples on the next page).

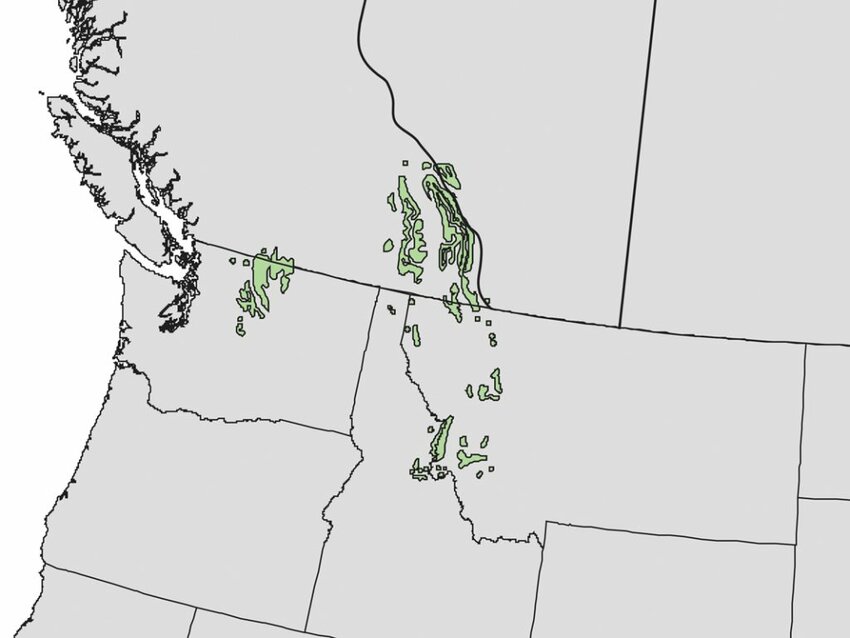

Alpine larch is one of two deciduous conifers native to the Pacific Northwest (the other is western larch, which grows at lower altitudes). They are conifers because they have cones and needles, but deciduous because they shed those needles annually. Alpine larches grow exclusively in a narrow elevation band in the Cascades (between about 5,000 and 7,500 feet) east of the crest, from the Wenatchee Mountains in central Washington north to about 13 miles inside British Columbia. Though locally abundant, the alpine larch’s range is only about 120 miles, north to south.

Why such a limited distribution? Given that they’re only found east of the crest, you might think that alpine larch requires a drier climate. Not so! The trees grow in cold, snowy and wet places – they’re found in the coldest and wettest parts of an otherwise hot and dry landscape. Mean temperatures are below freezing for more than half of the year in alpine larch habitat. The trees do best in high, north-facing cirque basins near the base of talus slopes where the soils are kept moist throughout the summer by water from snowfields melting above. The cool growing seasons at these locations last about 90 days and mean temperatures are less than 42 degrees Fahrenheit. The alpine larch prefers acidic soils and is often associated with granite or quartzite rock types, further limiting the areas in which it can thrive.

Alpine larches live a long time, as you might expect of a tree growing in such inhospitable terrain. Although 400-500 years is a common life span, many reach 700 and the oldest are estimated to be about 1,000 years old. They are slow growing as well; a 5-inch diameter tree is likely 150 years old and mature 20-inch diameter trees are likely over 500 years old. They typically reach 40-50 feet high – a surprisingly large tree for their high-altitude habitat. The largest recorded alpine larch, found in the Wenatchee National Forest, stands 95 feet tall and is 79 inches in diameter.

Alpine larch is also about the most shade intolerant species of conifer. It forms a forested band at the uppermost edge of where plants can survive, and above the limit of other tree species that might shade them out. The climate here is not only very cold; it is also extremely windy. Hurricane-force winds are common year-round with passing storms. They are able to survive in these harsh conditions by shedding their needles each fall – limiting water loss during the winter – in addition to having surprisingly supple branches that are less prone to wind damage. These adaptations to the alpine world mean that alpine larches rarely grow into the stunted and scrubby “krummholtz” form so common with other conifers at the tree line. It is striking to see a grove of tall larch trees growing against the craggy backdrop of summits, talus and snowfields, where there would only be a stubby tundra west of the crest.

These factors only converge in a narrow band within a small area of the Cascades. You can’t hike into the alpine just anywhere on the east side and find them, though they grow in more places than you might think. The brief window for peak color is the main larch hunting challenge. While the larch needles will start to change in September, the intense gold of the full show is remarkably consistent year to year, peaking the first week of October and only lasting for about a week. That’s because, like leafy deciduous trees, the changing color is tied to day length, with the trees shutting down chlorophyll production (the green) in anticipation of the coming winter. This allows the gold pigment that was always there to shine through. Strong fall storms can knock the needles down quickly in some years, but even during good weather there are only about two weekends for prime larch viewing.

Check out the trails below, or, armed with maps, trail descriptions and knowledge of the life history of the alpine larch, ferret out your own stash of golden larches. Happy hunting!

Alpine larch trail sampler

Location: North Cascades Highway - Hwy 20

Length: 7.2 miles roundtrip

Elevation: 2,000-foot gain, high point of 6,650 feet

Description: wta.org/go-hiking/hikes/maple-pass

Location: North Cascades Highway - Hwy 20

Length: 4.4 miles roundtrip

Elevation: 1,050-foot gain, high point of 6,254 feet

Description: wta.org/go-hiking/hikes/blue-lake

Location: Manning Provincial Park - Crows nest Highway - Hwy 3.

Length: 13.8 miles roundtrip

Elevation: 3,800-foot gain, high point of 7,949 feet

Description: env.gov.bc.ca/bcparks/explore/parkpgs/ecmanning/frosty.html

Based in Mount Vernon, Jason Griffith is a fisheries biologist, member of Skagit Mountain Rescue, husband and father of two young boys. Accidents aren’t allowed when he heads to the hills with the Choss Dawgs.