Story and photos by Ben Whitney

Story and photos by Ben WhitneyNot exactly the poster children for environmental crisis, zebra and quagga mussels and other invasive freshwater species have not been known to inspire the hoo-rah mitigation efforts seen for other noxious critters until they’ve already made their mark. Every bit as problematic as tree toppling bugs like the emerald ash borer, or the fragile alpine shrub-mowing mountain goats removed by helicopter from Olympic National Park in the 1980s, these mussels make quick work overthrowing long established ecological hierarchies. What these freshwater invaders might lack in sex appeal, they make up for tenfold in the havoc wrought on the waterways they rapidly colonize.

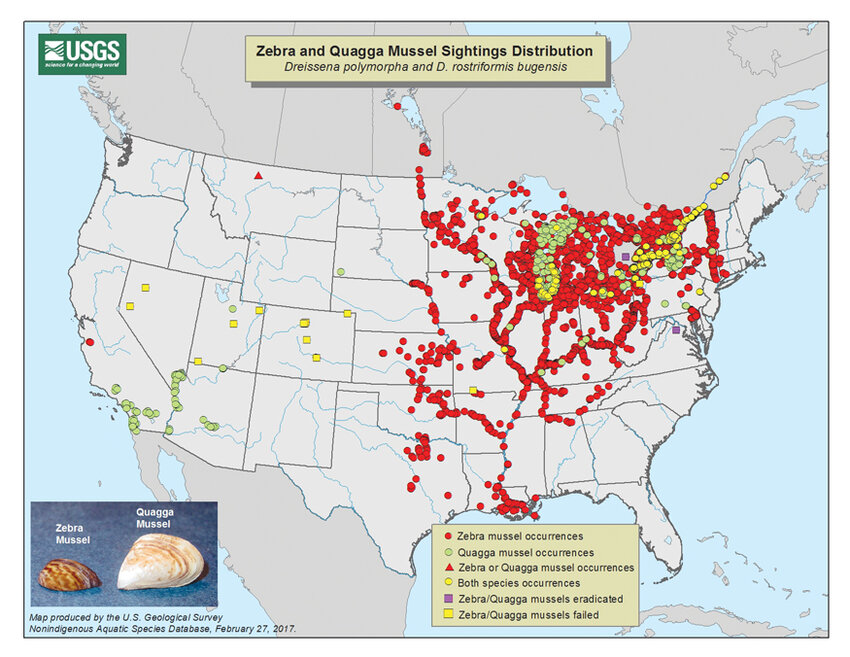

Zebra and quagga mussels, native to Russia and Ukraine, haven’t yet reached the Pacific Northwest, but they creep closer every year and are within a day’s drive. In the Great Lakes these mollusks are now the most common invasive species, and they’ve irrevocably altered the region’s freshwater ecology. From the Great Lakes, these mussels have spread along Midwestern waterways and by trailered boats to areas even closer to the Pacific Northwest like California, Nevada and Montana.

The City of Bellingham has taken a decidedly preemptive approach to tackling an issue that has affected North American water bodies for decades. In 2012, the Aquatic Invasive Species (AIS) program launched an effort to prevent zebra and quagga mussels and other aquatic hitchhikers from establishing colonies and spreading throughout Whatcom County’s waterways. Program coordinator Teagan Ward says that community members have reasonable cause for concern.

The City of Bellingham has taken a decidedly preemptive approach to tackling an issue that has affected North American water bodies for decades. In 2012, the Aquatic Invasive Species (AIS) program launched an effort to prevent zebra and quagga mussels and other aquatic hitchhikers from establishing colonies and spreading throughout Whatcom County’s waterways. Program coordinator Teagan Ward says that community members have reasonable cause for concern.

“In some areas, like the Great Lakes, have managed to clog pipes, impact water quality, and cause taste and odor issues,” Ward says. “All of those things end up costing millions of dollars to manage.”

Further, these mussels are easily transported in ballast tanks, live wells or by attaching to a boat’s exterior. Cause for special concern is the fact that Lake Whatcom and Lake Samish act not only as recreation destinations, but also as drinking water reservoirs - an unusual combination. Drawing from policy and regulations applied in other western states, most notably at Lake Tahoe, California, Bellingham developed an inspection and monitoring program of its own. And nearly 30,000 inspections later, the AIS program entered its sixth season this April. Each inspection, Ward explains, is an opportunity to educate boaters and encourage participation.

“We’ve had almost 5,000 people take our online awareness course since 2014,” she says. “That’s really exciting because we know exactly the level of education they’ve received by having to pass a test at the end.” And for their participation, boaters are rewarded with a $10 discount on annual permitting fees.

This season, Ward leads a staff of 16 inspectors stationed across three boat launches on Lake Whatcom and one at Lake Samish. Each lake will be staffed seven days a week from dawn to dusk for the duration of the fishing season. This first-of-its-kind program in Washington state has made some impressive contributions to AIS management.

As of 2016, all permitting is digitized using a database designed by Bellingham’s IT wizard, Matt Bezanson, in collaboration with Ward and her team’s needs. The database reduces paperwork while increasing the accessibility and accuracy of information. But most importantly, it makes inspections more efficient so that boaters can get on the water quickly. Some of the collected data is available publicly, in what Ward refers to as, “storymaps,” which provide visual representation of boat profiles, their waterbody history and their associated risk.

As of 2016, all permitting is digitized using a database designed by Bellingham’s IT wizard, Matt Bezanson, in collaboration with Ward and her team’s needs. The database reduces paperwork while increasing the accessibility and accuracy of information. But most importantly, it makes inspections more efficient so that boaters can get on the water quickly. Some of the collected data is available publicly, in what Ward refers to as, “storymaps,” which provide visual representation of boat profiles, their waterbody history and their associated risk.

Looking forward, the AIS program hopes to build on relationships with other local, state and interstate agencies while also continuing to develop a participatory relationship with lake users. Citizen science, Ward believes, provides a platform to continue encouraging participation. “We are increasing awareness in the community and I’d like to go a step further and empower members of our community already out their paddling on our lakes to look for species,” Ward says.

Monitoring efforts have yet to find zebra or quagga mussels at Samish or Whatcom. Other invasives, introduced prior to the program’s launch, are being carefully tracked and contained. But results are admittedly challenging to measure when it comes to prevention programs where tangible results, like finding a mussel attached to an outboard propeller, are bad things.

“My biggest goal is to encourage as much participation as possible,” Ward says. “I want people to follow clean, drain and dry practices whether I’m standing there or not.” And ultimately, Ward believes that by encouraging participation and empowering boaters to follow these practices, the AIS program will effectively foster a clean water future that extends far beyond the waters of Samish and Whatcom.

Clean, Drain, Dry practices

• CLEAN watercraft, trailer, motor, and equipment. Remove visible aquatic plants, mussels, other animals, and mud before leaving any water access.

• DRAIN water from boat, bilge, motor and livewell by removing drain plug and opening all water draining devices away from the boat ramp. Regulations require this when leaving accesses in many states and provinces.

• DRY everything at least five days before going to other waters and landings or spray/rinse recreation equipment with high pressure and/or hot water (120°F/50°C or higher).

Inspired by the allure of the North Cascades, Ben Whitney moved to Bellingham from Vermont this winter. He writes about people, place and community, and is excited to contribute to the creative wellspring that surrounds the alpine.