Photo by Andrew Waits

Photo by Andrew WaitsBy Jason Martin

It was August and there was almost no snow left on the glacier. The lower Coleman was cooking under the late summer sun as American Alpine Institute guide Jeremy Devine taught ice climbing skills to a group of students.

The team was lounging on the edge of the glacier when one of them noticed something.

“There was some old white rope with blue prussiks on it and a snow fluke,” Devine said. “There was also a blue pack with an orange strap sticking out of the ice. I had to

chop it out.”

When the team finally pulled the ancient pack from the ice, they found a name scrawled on the pack in black permanent marker: S. Raschick

August 3, 1986

The northern lights danced in the sky above Mt. Baker, providing a brilliant fireworks display of flashing color. The light was so bright that it pulsed on the frozen snow, lighting the way for the solitary rope team inching its way up the Coleman Glacier.

Ian Kraabel, a 23-year-old mountain guide at the beginning of his career, led the young team. Following in his footsteps were a pair of 21-year-olds, Steve Raschick and Kurt Petellin. And finally, at just 19 years old, followed Tom Waller.

It was 1986, and it was already one of the most tragic years in U.S. mountaineering history. In May, seven students and two faculty members from the Oregon Episcopal School died of hypothermia on Mt. Hood.

As the team moved up the glacier under a breathtaking light show, the team didn’t think about that tragedy. Instead they were focused on their ascent and their summit, oblivious to the fact that they were about to experience their own tragedy.

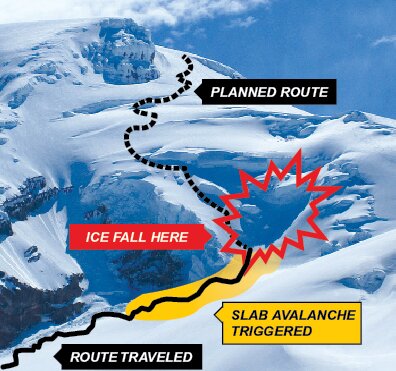

The team took a break at the 8,500-foot level. It was there that Kraabel proposed a different route up the mountain, one other than the standard Coleman-Deming. He pointed out the steep snow ramp that cut up the mountain face between the Roman Nose and the Pumice Ridge, a line known as the Roman Moustache or simply as the Moustache.

“It’ll be faster,” he said. “We’ll get up to the top more quickly and then we’ll be down earlier.”

Both Steve Raschick and Kurt Petellin were big men, and they were struggling a bit on the ascent. They decided to listen to their guide’s advice. Tom Waller looked up to Raschick. He was like a big brother figure to him. So he decided he was going to do whatever Steve did.

The Moustache is not a beginner route. Indeed, it is an intermediate route that, depending on the year and the exact line, ranges from 40 to 55 degrees steep. The American Alpine Institute regularly guides it at a ratio of no more than two climbers to one guide, and they only guide it with people who have ice-climbing experience. The three men Kraabel led that day only had two days of prior training, and the focus of that training was on glacier travel and crevasse rescue.

The team left their breakpoint and began to move up the mountain, making their way up the initial ramp on the Moustache. As they moved, the team stayed in glacier travel mode instead of transitioning into pitched climbing as the terrain got steep. Additionally, both Raschick and Petellin were having problems staying on the snow’s surface. The pair kept breaking through the crust to the deep and wet isothermal snow beneath, which made travel up the ramp a slow and exhausting endeavor.

Suddenly there was a loud crack.

“I looked up,” Tom Waller said. “I saw ice coming down above Ian, and that’s when the sky fell.”

A serac above the route calved off, dropping refrigerator-sized blocks of ice into the snow above the team. The blocks splashed down into the snow like it was water, displacing everything and triggering a massive avalanche. The slide exploded down the slope, a mix of broken ice blocks and wet snow. It hit the team like a white wall, blowing them off the side of the steep slope.

“It was like we were being erased,” Waller said.

A crevasse cut across the glacier below the slope. Kraabel, Raschick and Petellin were all washed into the crevasse. Waller was thrown over it.

Then everything stopped. There was complete silence.

Photo by Jason Martin, graphics by Doug De Visser

Photo by Jason Martin, graphics by Doug De VisserThe sun rose over the tragic scene, lighting up the mountainside with golden morning light.

When Waller opened his eyes, the first thing he saw was a scarlet streak of blood on the snow next to him. At first he thought he’d been injured by the ice axe, but then he started to cough. And with each cough, more blood speckled the snow. He had a punctured lung.

“I didn’t know what had happened. I thought, ‘was that an avalanche?’ And then I remembered Steve and Kurt. I started yelling for my friends.”

Waller yelled as loudly as his broken body would allow. But there was no response, just the echoes of his voice ringing off the snow slopes surrounding him.

Approximately 20 minutes after the avalanche, another team of four arrived on site. Brothers Steve and Tim Sieberson, as well as Larry Bouma and his son Jeff sat Waller on a chunk of ice while they searched for survivors.

Like the other three, Petellin was blown off the mountain by the avalanche. In a frantic attempt to survive he “swam” to the surface of the slide. But it didn’t matter – he was still washed into the crevasse. “I remember hitting the downhill side of the crevasse and that was it.”

When the fog cleared, Petellin found himself hanging upside down, one foot pinned in the debris. “I used the snow fluke to dig my legs out,” Petellin wrote in an email. “I had to dig my left foot out all the way to the top of the crampons to free it.”

Petellin placed an ice screw, clipped himself to it and began to yell for his friends. “I was calling for Tom, Steve and Ian, and letting them know that I was going to dig them out.” He continued heroically to fight for his friends until the rescue party extracted him.

Neither Ian Kraabel, nor Steve Raschick were so lucky. They were gone. Buried in the crevasse.

A Vancouver Search and Rescue Unit was on the mountain training when the accident happened. They were able to establish radio contact and requested a Navy helicopter for the evacuation. By noon that day, both Waller and Pettelin were undergoing treatment for their injuries at a hospital.

Several weeks later a party discovered Kraabel and Raschick. The late summer melt ate away at the avalanche and eventually revealed the two bodies. It was determined that they both died instantly of trauma and did not suffocate, which was of some small solace to the survivors.

Clearly, Ian Kraabel made some mistakes and those mistakes cost both him and one of his guests their lives. But it’s hard to blame him.

In 1986 there were very few resources available for a young new guide to get trained in the United States. Most established guide services were doing all of their training internally. Modern avalanche training almost didn’t exist, and the American Mountain Guides Association (AMGA) was still in its infancy. It would be almost a decade before the AMGA national guide-training program would come online.

Steve Raschick’s backpack was still on his back when the avalanche struck at nearly 9,000 feet on Mt. Baker. It’s not known if the recovery team removed the pack and left it or if it was torn from his body by the slide. Twenty-nine years later, the pack surfaced at approximately 5,200 feet. The pack had traveled nearly 4,000 feet down the mountain, most likely under the ice the whole time.

Jeremy Devine found Tom Waller through a post on mountainproject.com. They met early in the morning in Fairhaven before Devine was slated to head back out into the field to guide another trip.

Devine handed a brown paper Fred Meyer bag to Waller. Inside were the items that he’d found on the mountain. It would be several days before the now 48-year-old Waller would open the bag.

“Steve was my world. He was my best friend,” Waller said emotionally. “I just want people to remember him. I just want people to remember that he was here and that he mattered…” x