Alex Kollar (1993-2021)

Adventures are like bus stops on the way down memory lane. One stop in particular has become all too familiar. It was a rare mid-winter ski traverse through the heart of the Alpine Lakes Wilderness with my friend Alex Kollar. What we found together was a Shangri La bathed in sunshine and endless fields of powder. More importantly, what I found was a new friend worth planning future adventures with, a rare individual who enjoyed my brand of suffering and exhilaration in the mountains.

Alex was a guy who smiled after he went headfirst into a creek and grinned when I explained I'd gone ass over teakettle through the forest. When we finished our four-day traverse and prepared to drive out, Alex saw a father and son stuck on a muddy side road. He didn't hesitate to wade through the mud barefoot to push them out, and laughed like a maniac when we got stuck in the same predicament a few moments later.

I will never forget Alex's go-to "Yeah, buddy" on a great downhill run. I'm sure he brought that same enthusiasm to the Deschutes River in Oregon. Sadly, he never made it out this October.

I will never forget Alex's go-to "Yeah, buddy" on a great downhill run. I'm sure he brought that same enthusiasm to the Deschutes River in Oregon. Sadly, he never made it out this October.

So now, when I'm riding down memory lane, I find myself stopping on this adventure. Step off the bus with me, and enjoy the journey!

As snows fall and winter winds march across the Alpine Lakes Wilderness, this mecca so many hikers tread and trod from one end to the other reverts back to a no-mans land, winter bound and silent except, that is, for the occasional backcountry skier, like myself. For us, winter isn’t a barrier but a means to an end. Snowbound valleys become canvases to cut fresh trails across and snow-coated mountains become playgrounds to summit and descend from.

When it comes to winter wonderlands, few places curl up in my soul and become a part of me through and through as much as the Alpine Lakes Wilderness has. A direct result of not only my fascination with its sharpened pinnacles and bejeweled valley’s full of sparkling lakes, but because I get to visit this region over and again, year after year, and see the shift and shuffle of change in the world without, while time remains frozen in the wilderness within.

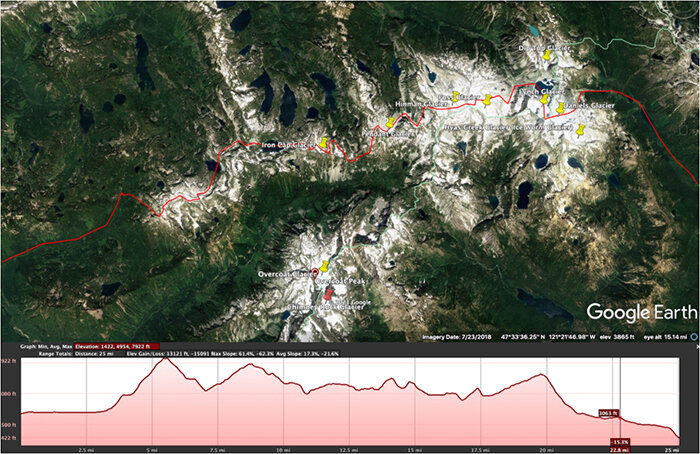

Variations of the Alpine Lakes Traverse have long interested me, but inspiration to tackle this particular version, which goes from Mt. Daniel to Big Snow Mountain, came from my need to visit glaciers for my Washington Glacier Ski Project. These glaciers included the Dip Top, Iron Cap and Pendant glaciers.

March 9: Deception Pass Trailhead to Pea Soup Lake, Mt. Daniel Summit

March 9: Deception Pass Trailhead to Pea Soup Lake, Mt. Daniel Summit

Under the heels of an angry snowmobile, 11 miles of road swept by in a spray of ice that thwapped my head. The praying sort would ask not to be keeled under sled tracks or dragged hogtied by a heavy pack across the icy road, but I like danger, it turns out, for about 10 miles. Only 11 miles of road later, Jake and Matt, who piloted Alex and I to the trailhead on their stallions, finally pulled up at the end of the road.

Jake and Matt joined us on the ascent of Mount Daniel. While there are many approaches to the summit, for expediency’s sake, we bypassed Cathedral Peak and made a direct ascent of the mountain. We toured past Hyas Lake (Hyas means ‘big’ or ‘great’ in Chinook jargon) and ascended a couloir I dubbed Killer Cornice Couloir because, of course, it’s as much a killer place to have lunch as standing under a crane that’s moving a piano to the top story of a city apartment.

Some few hours later, in a cold huddle near the top of Mt. Daniel, Alex and I split ways with Jake and Matt who were returning to their stallions and town, to cold beers and warm beds. While they vanished into wind and fog, Alex and I continued upward, soon becoming lost in the white miasma. Having been to the summit of Daniel a dozen or more times, I set out confident that I knew the way. Only, in reality, I didn’t. When we reached a summit we discovered that it wasn’t actually the summit at all, but the top of the east peak of Mt. Daniel.

With the help of the ‘of course, you’re right’ GPS, we made our way to the actual summit. Bruised dignity aside, the slow shuffle around the summit towers brought me back to the present. A distracted mind could, say, be unknowingly walking the plank, since cliffs abounded above and below, appearing in and out of the fog like ghouls.

All day (even with evidence to the contrary) our expectation was that the sun would grace us with her light. Instead reality provided a face full of graupel and the omnipresent buzzing of metal that comes with a charged atmosphere. A sure sign that it’s time to not be standing on the highest point around. Even so, I yelled to Alex, “Look at those beautiful lakes and how about that Lynch Glacier? What a view!”

We laughed and retreated to a small pass just above the aforementioned glacier and from there dropped toward Pea Soup Lake.

Like two sea captains, we piloted our skis through the fog and somehow remained standing. After we arrived at Pea Soup Lake, I canonized the moment by saying to Alex, “How appropriate to arrive at Pea Soup Lake in a pea soup fog.” In the wind and snow I couldn’t tell if he laughed or groaned.

Midway across Pea Soup Lake, fog retreated and revealed our descent tracks. They were as if two children were given a white wall and markers to scribble with. Alex quelled my embarrassment over our ski signatures when he assured me that, “The snow will cover them by morning.”

Midway across Pea Soup Lake, fog retreated and revealed our descent tracks. They were as if two children were given a white wall and markers to scribble with. Alex quelled my embarrassment over our ski signatures when he assured me that, “The snow will cover them by morning.”

March 10: Pea Soup Lake to Pea Soup Lake to Iron Cap Pass, Mt. Hinman Summit

Calm winter mornings are as silent as they come. Attempting to not break that peace and quiet, I crept out from the tent like a child from his room on Christmas morning. My present was a solo side trip to Dip Top Glacier. On my way there, the slopes unwrapped from behind ridges. As I crept up powder-filled slopes, I felt the kind of thrill only the unexpected fulfills.

Atop Dip Top Gap I skied onto the now-stagnant north facing Dip Top Glacier toward Jade Lake. In the midst, alone among all that disappearing ice, looking out onto a horizon of peaks, I felt that I was among friends, however non-corporeal they may be. Friends are always there for you, as are these peaks.

Back at camp, I rejoined Alex and we herded our gear into packs and descended from Pea Soup Lake to the valley below in a daze. For, there it was, that sunny powder we’d been jiffed of the day before. Our surging thrill came in waves, like the snow that was sent flying with each turn.

Hearts quieted after a short but earned for descent. After which we climbed the Lower Foss Glacier and the gentle slopes of Mt. Hinman whose slopes I’ve found unusual. Glaciers tend to create steeper north faces than south faces, in general. Hinman bucks the trend.

When we arrived to the crest of the ridge, the views assaulted us like scantily dressed ladies at a ball.

When we arrived to the crest of the ridge, the views assaulted us like scantily dressed ladies at a ball.

We tore ourselves from the views and traversed Hinman Peak until we descended to La Bohn Lakes. As I skied toward a blind rollover, I thought Alex waved me on. Just a few feet before the edge, I hockey stopped on icy snow, the worst we had the entire trip, and only then learned from Alex that his wave was telling me to stop. Because I couldn’t help myself, I did some quick and dirty math and my former trajectory didn’t add up to anything pretty.

With my excitement sufficiently checked, we descended the remaining slopes to Necklace Valley and from 4,900 feet we climbed onto the Pendant Glacier. Cloud shadows chased us across my second un-skied glacier of the trip. While I’d hiked through this terrain often, I find skiing through it so very different. In the winter, the high country reverts to its natural self: Wild and untrammeled.

Across Upper Tank Lakes was only recognized as a lake as I’d been there in summer. About halfway to Iron Cap, along a gentle bench, the views of the mountains grabbed us up and steered our skis to the rim of the valley. By the time the glamour was broke, dusk and sunset were upon us, so we decided to drop packs and camp. Sometimes stopping is worth hurrying into, the only distance worth gaining. When going further doesn’t get you anywhere that matters.

March 10: Iron Cap Pass to Gold Lake, Iron Cap Summit

A lazy and tranquil morning drew out the hours and before we knew it, noon was fast approaching. Since a warm day was bad for a crossing beneath Iron Cap, our tardiness was a regrettable oversight. Fortunately, conditions remained stable, but by then worry had already lit a fire under our asses, so we made short work of the mile-long traverse and boot pack to the crest of the north ridge. Slower, though, was the serpentine ridge to the summit; we couldn’t help but stop every 10 feet to take in the views ahead and behind us.

A lazy and tranquil morning drew out the hours and before we knew it, noon was fast approaching. Since a warm day was bad for a crossing beneath Iron Cap, our tardiness was a regrettable oversight. Fortunately, conditions remained stable, but by then worry had already lit a fire under our asses, so we made short work of the mile-long traverse and boot pack to the crest of the north ridge. Slower, though, was the serpentine ridge to the summit; we couldn’t help but stop every 10 feet to take in the views ahead and behind us.

Immediately below us was the Iron Cap Glacier, which is stagnant ice today. The lake at the bottom is one of those newly formed in recent decades, a left over from glacier retreat much as the lower altitude lakes were leftovers from the last glacial surge of the Puget Arm of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet about 16,900 years ago.

Instead of wrapping around the shoulder of Iron Cap Peak, we decided to ascend 500 vertical feet over a ridge for a direct descent to Chetwoot Lake. At the top once more, another field of powder lay below, just as drool-worthy as the last, and after we ate up the vertical like starving shipwrecked survivors, we coasted onto the lake. All along the way sun speared through clouds, snow blasted around skis and we found ourselves suddenly stopped, feeling lighter no matter our heavy packs.

While we could either go over Wild Goat Peak or around it, we chose the more conservative route. It turned out to be the right decision. We found terrible snow on our ski to Gold Lake. We pitched camp on the lake ice and after the sun went down, I watched the starlight glint on snow crystals as I cooked a mountain feast fit for only hungry climbers.

While we could either go over Wild Goat Peak or around it, we chose the more conservative route. It turned out to be the right decision. We found terrible snow on our ski to Gold Lake. We pitched camp on the lake ice and after the sun went down, I watched the starlight glint on snow crystals as I cooked a mountain feast fit for only hungry climbers.

March 11: Gold Lake to Dingford Creek Trailhead, Big Snow Summit

Morning awoke to light spreading across Big Snow Mountain and Gold Lake. Alex and I didn’t budge a muscle until it rolled over us like a slow rising tide. Eventually, resigned to our last day, we gathered gear and skinned across the lake toward a serpentine streambed. This led us from the flat, frozen lake toward gently rising and rolling terrain, which offered easy access to the uppermost slopes of Big Snow Mountain.

I’d like to say that a summit doesn’t attract me, but I’d be lying if I said it didn’t. What’s more is that the best traverses in my mind are those that add summits and descents in conjunction with horizontal movement across or along mountain ranges. That’s why going over the summit of Big Snow was part of this adventure. It shows how much work there is to do out here in this tiny corner of the Cascade Mountains. These (big) little peaks that surrounded us have character; different moods and faces that keep all of us guessing as to their true nature.

Once our boards were snapped on, our reward besides the views, which were kid in a candy store kind of ‘google-eyed’ awesomeness we never get enough of, was the descent. Striking down the west shoulder of the mountain was a beauty of a line that would be the gobstopper of the trip. Usually I would take photos of such a descent, at least a few, but this time I put my camera away. Even a few shots can distract me from having fun of my own. Besides, soul turns mean soul turns.

Once our boards were snapped on, our reward besides the views, which were kid in a candy store kind of ‘google-eyed’ awesomeness we never get enough of, was the descent. Striking down the west shoulder of the mountain was a beauty of a line that would be the gobstopper of the trip. Usually I would take photos of such a descent, at least a few, but this time I put my camera away. Even a few shots can distract me from having fun of my own. Besides, soul turns mean soul turns.

And on the descent my ‘soul’ sang. Sadly, what also sang, except out of tune, were my legs. Not wanting to stop, I careened down the slope like a runaway train. Somehow I didn’t yard sale. Neither did Alex. After our final turn, we pointed our skis back up at the line. As it came into view, smiles grew, and I silently promised to get more ‘soul turns’ in the near future.

Every valley in Washington begins in the Cascade Mountains and every mountain in the Cascades Mountains ends in a valley. So it was that we descended into the forest. Between losing the trail and for the fact that there wasn’t quite enough snow to cover logs, rocks and debris, we were like a ski ballet troupe doing never ending practice rounds where we ducked and stepped, bent and danced, tripped and fell and, well, you get the point.

There was a point when Alex, caught up in the rhythm of our race down trail, when he was swept up by the rocks and cast sidelong into a creek. Swimming and skiing don’t usually go hand in hand, so when it happens there’s a full helping of laughing, moaning and, after which, the race goes on.

A few hundred yards before the end of our trip, I laid down my skis after going far too long on too little snow (something I’m more proud of than I should be), and waited for Alex.

It’s important to take a moment to look over any adventure you’re on and take it all in — to give it its due in the moment, not after, when you’re home. It’s been a crazy year with Covid-19, and ski adventures took a back seat for the first time in my life. That is why this adventure felt rejuvenating for me, a reminder of why I still push myself to go to these places. Yet, it also reminded me how much they mean to me, not in that I can’t exist without it kinda way, but in that I feel at home out here kinda way.

When Alex arrived, we walked the final yards to the truck and to beers of our very own.

When Alex arrived, we walked the final yards to the truck and to beers of our very own.

Later, as we were helping a stuck father and son pull their rig from their proposed camping spot above the Middle Fork Snoqualmie, sans shoes and in ski clothes, Alex and I had to laugh when our kindness resulted in us also getting stuck. “At least we have our camping gear,” I told Alex.

Fortune was with us, though. A couple with a winch drove by just as dusk was falling. With their help we were once again on our way, mud splattered and thankful. It just goes to show, the adventure isn’t over even after you’ve returned to civilization.

Find a video Alex made of the trip here. x

Jason is an outdoor adventure photographer based in Gig Harbor. He’s currently working to ski every named glacier in Washington State. Find his stories and imagery at Jasonhummelphotography.com.