“There’s nothing worse than a sharp image of a fuzzy concept.” – Ansel Adams

The sun is setting over the Pacific. The exposure is spot-on, the focus sharp, the composition clear … and the photo is boring. At best, it gets a shrug from viewers.

As Ansel Adams’ quote indicates, technical perfection doesn’t make photos interesting. In contrast, look at Robert Capa’s famous images of the D-Day invasion of Normandy. The photos are blurred and grainy, but they endure because they capture the chaos and madness of combat for those who have never experienced it.

Let’s delve into how to convey meaning with photographs. After all, photography is a means of communication. Light and visual language are how we say things, but first the photographer must have something interesting to say.

What is Photographic Meaning?

Photographic meaning is different from literal meaning. Photographs must communicate with someone the photographer will never meet, and photos often must stand alone without text, captions or control of the viewing experience. Meaning therefore requires intense distillation. If you can’t describe the meaning you’re trying to convey, you probably won’t be able to make a compelling image.

Narrative vs. Evocative Images

It’s useful to think of images that narrate a story and those that evoke emotions, although some will do both.

Narrative images tell a story in a factual way. Purely narrative images rarely stand the test of time, unless they contain emotional content or narrate a significant event, like the UPI image of Jack Ruby shooting Lee Harvey Oswald. When images are presented together, narrative photos can set the stage for evocative images that follow.

Photos that evoke emotions pack far more punch. Think of universal emotions; love, fear, humor, passion and mystery. Evocative photos can have impact even without much information. The image of my two-week-old niece looking like Winston Churchill never fails to get a laugh. (Image 1)  There’s no story – she was just figuring out how her limbs worked, and struck the pose for a split second. One of the most famous images ever made, Steve McCurry’s “Afghan Girl” (http://bit.ly/1axJcZO) tells us nothing about where it was taken or what led to the girl’s haunting look. It’s not necessary. The emotion is enough.

There’s no story – she was just figuring out how her limbs worked, and struck the pose for a split second. One of the most famous images ever made, Steve McCurry’s “Afghan Girl” (http://bit.ly/1axJcZO) tells us nothing about where it was taken or what led to the girl’s haunting look. It’s not necessary. The emotion is enough.

Since the Mount Baker Experience is an outdoors magazine, what emotions drive us? The peace of a week away from civilization? Bone-deep, well-earned exhaustion after a long climb? The clench in the gut dropping into a big rapid? The only thing that makes Image 2 a kayaking image is the silhouette of the paddle. It’s an emotional image because it evokes both peace and the sense of a journey.

a kayaking image is the silhouette of the paddle. It’s an emotional image because it evokes both peace and the sense of a journey.

Mature and Immature Subjects

Pioneering climbing photographer Galen Rowell distinguished between immature and mature subjects. An immature subject is one that viewers don’t understand without a fairly literal depiction. Mature subjects are things we’re already familiar with and therefore work on an evocative level because we have an established context. Image 3 only makes sense if you’re familiar with the Buddhist tradition of burning incense to purify and invite spirits. The smoke is a metaphor for religion’s quest to provide answers to mysteries, and the blurred face allows the woman to represent all humanity’s search for meaning.  Most western viewers, unfamiliar with Buddhist traditions, can only interpret this photo’s meaning if it’s preceded by narrative images to set the scene.

Most western viewers, unfamiliar with Buddhist traditions, can only interpret this photo’s meaning if it’s preceded by narrative images to set the scene.

Two Ways of Evoking Emotions

Photographs evoke emotions in two ways: equivalence and metaphor.

Minor White described equivalence in 1963. He would find the emotive kernel of a scene or experience, then use the tools of light and visual language to make the viewer of his images in a gallery miles away and years later, feel the same emotion. Since visual language is so deeply programmed into human consciousness, a skilled photographer can evoke the desired emotion in a way that the viewer doesn’t know why they feel peace, tension or regret when they view an image. But they do, because the photographer has put subtle visual cues in place.

This image of two-time youth champion Eli Nicholson at the Roaring River Slalom is an example. (Image 4)

The topic is concentration and focus, but there’s no particular look of concentration on Eli’s face. It’s conveyed via other visual cues: the saturated colors, the green moving water and the blood-red color of the gate he’s striving for. The black background makes it so that nothing exists but the water, the gate and the racer; which is exactly how it feels to compete.

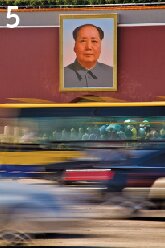

Moby Dick is about more than a man chasing a whale. Like novels, photographs use metaphors to imply meaning. Image 5  was taken of Mao’s portrait above the entrance to Bejing’s Forbidden City across from Tiananmen Square. Mao both watches over daily life from a higher plane, and remains static as the world moves by. Taken at the epicenter of the 1989 uprising, this image evokes an authoritarian, surveillance-obsessed government watching over its citizens. Simultaneously, it conveys a sense that the rapid modernization of daily life is passing the communist ideology by posing a fundamental conundrum for China. Mao’s portrait hangs from the famous entrance to the emperor’s old palace, evoking a succession of dynasties and dictators. Meet the old boss, same as the even older boss. All these interpretations can exist side-by-side in an image.

was taken of Mao’s portrait above the entrance to Bejing’s Forbidden City across from Tiananmen Square. Mao both watches over daily life from a higher plane, and remains static as the world moves by. Taken at the epicenter of the 1989 uprising, this image evokes an authoritarian, surveillance-obsessed government watching over its citizens. Simultaneously, it conveys a sense that the rapid modernization of daily life is passing the communist ideology by posing a fundamental conundrum for China. Mao’s portrait hangs from the famous entrance to the emperor’s old palace, evoking a succession of dynasties and dictators. Meet the old boss, same as the even older boss. All these interpretations can exist side-by-side in an image.

Creative Tips

Here are some ways to jumpstart your creative

thinking:

Write down words. Before you photograph something, write down as many words about it as you can. To demonstrate, think of an egg: words that come to mind may be white, oval, food, fragile, natural, growth and cholesterol, for starters. Then make one of these words the theme of your image. The same exercise will help you develop themes for travel destinations, sports and people.

Consider the invisible. Remember that photos can’t convey sounds, smells or the feeling of crisp cold air, yet these are huge components of our experience. Give yourself assignments like the smell of rain, the crunch of tires on a gravel road, or whatever non-visual cues enrich your experience. Then find non-literal ways to convey them.

Photos don’t need to be pretty. There’s always room for more beauty in the world, but don’t become stuck on making classic postcard shots. If your goal is to evoke tension, challenge or questioning, beauty may not be the best tool.

Find contrasts and similarities. Seek images where there’s either an obvious conflict, such as in Image 1, between an infant and a very adult pose, or similarities between dissimilar things.

Embrace mystery. Unanswered questions create suspense. A hallway leading into dark, inky shadows hints at something about to reveal itself. (Image 6)

Group assignments: Assemble a group of people and pick a theme with many interpretations. Go shoot on your own, then gather to see the many interpretations. Seeing others’ work will help improve you own.

Neil Schulman is a writer and photographer based in Portland, Oregon. You can find his work at www.neilschulman.com/neilschulman2. x