Courtesy photo

Courtesy photoI did not know sea cucumbers move.

Yes, I’m aware they are marine creatures common in the North Pacific near-shore intertidal waters. Not vegetative beings, like gherkins. Echinoderms, as they are technically referred, are found worldwide.

And here they are, in the brisk waters of Ketchikan, Alaska, where I am watching some very large specimens gather for a meeting on a sidewalk pavement-size, slanting slab of rock about 5 feet deep. Their commute is best called creeping, but it is visible movement, a revelation to me. I can’t tell you why they are clumping together … coffee break, perhaps, after a hard morning scavenging plankton and other oceanic organic debris. Vacuuming, in other words. I find that hard work, too, and a rest break is welcome.

Right now, the hard work for me is floating around a small cove on the Tongass Narrows at Ketchikan’s Mountain Point, snorkeling in a neoprene wetsuit, a garment with a name that does not describe its effect. Put it on — like squeezing yourself into a blimp — jump in the 50-degree water and you become the Michelin Man, puffed up like, well, a sea cucumber. Movement is as laborious as running in mud, but at least it’s in water. Paddling hopefully into a light chop, from a distance I must look like a manatee.

However cumbersome, the suit makes possible this exceptional experience. Offered to Ketchikan visitors and residents by a soft adventure company called Snorkel Alaska, it moves one of my favorite tropical activities 3,000 miles north to an underwater landscape that I’ve always heard is as colorful as any coral reef. Skeptical of that, I signed up for this with a feeling similar to what you have when you turn on a Seahawks game.

I’m of little faith, it turns out. The only thing lacking here are reef fish that look like flags colored by Gauguin. Well, brain coral, too. But the Southeast Alaska subsurface canvas is an expressionist masterpiece rendered by Earth’s greatest artist.

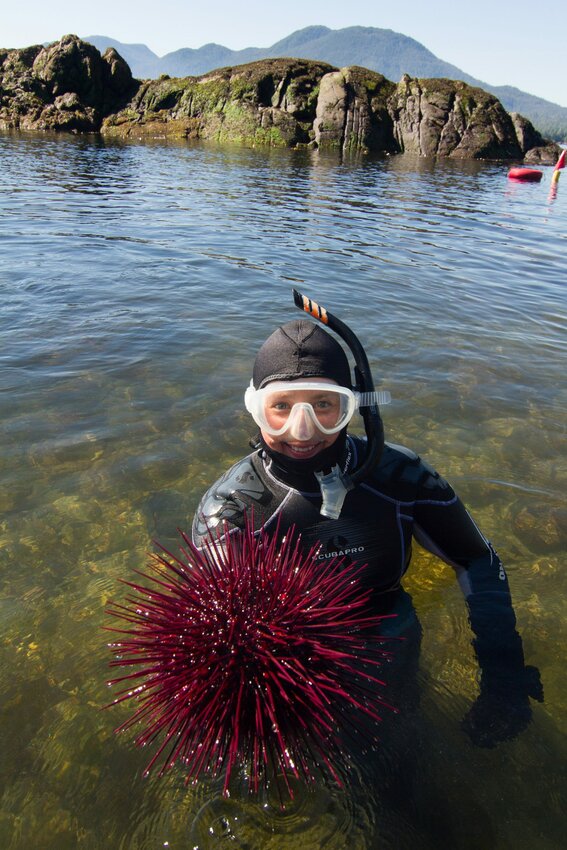

There are vivid orange and ivory nudibranchs. Sea anemones in gleaming chartreuse. The eelgrass forest hides crabs, sculpins, herring and other baitfish. A zillion sea urchins, more numerous and larger than I expected. Rockfish, lurking among … rocks. Shimmering crystalline moon jellies, drifting by like asteroids. Pulsating orange lion’s manes, small now as it’s early summer, but soon to reach 3 feet across.

All these underwater creatures are more numerous, more luminous and more enthralling than I ever imagined. I’ve seen them hundreds of times from the above-water vantage of a kayak or canoe, or draped on rocks at below-zero tides. Viewed through the prism of the ocean surface, they all seemed ghostly, distant and evanescent. Here in the water they are as palpable and present as a flower garden at my feet.

It’s an excellent sensory adventure, to be sure. It also illustrates up close a fact Alaska visitors know, but peripherally, like most people, have a dim and distant notion of a thunderstorm’s might until they are struck by one at timberline. This is the homeland of natural exceptionalism.

Alaska is full of bigs — tallest mountain (Denali), largest national forest (Tongass), largest national park, largest state. If you cut Alaska in half, goes a meme every Alaskan knows, each half would still be bigger than Texas.

Most pertinent today are the marine bigs. This little cove is a mote on the edge of Earth’s biggest ocean. The North Pacific third of it is arguably the richest environment on this planet: More biomass per square meter than tropical seas, marine biologists say. Alaskan waters hold one of the world’s biggest fisheries resources — 5 billion salmon a year — and are the highway for two of the world’s most amazing migrations, gray whales from Mexico and humpbacks from Mexico and Hawaii, thousands of whales traveling thousands of miles. Even the sea cucumbers are big, up to 2 feet.

All of that is remarkable enough, viewed from above. From within, it changes to a stupendous non-virtual reality, like transforming a spreadsheet into a kaleidoscope.

So we pilgrims have donned suits and carefully balanced our way across rocks into the water; been advised to take our time and keep our peers in sight (especially guides); cautioned against handling urchins and lion’s manes (duh) or for that matter, any of these subsurface denizens. Periodically we gather for show and tell, bobbing upright in the water like kindergarteners at summer camp.

“You’ve heard of sunflowers, right?” Our guide briefly holds up a 10-armed starfish the color of sunrise. “This is a sunflower star. Our summer flower, you know?”

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photoAlmost eradicated from more southern waters by a mysterious disease, sunflower stars here seem as hale and happy as bison in North Dakota. Same goes for urchins, which have been threatened by sea otters and commercial harvesters. Yearling salmon muscle past, glistening platinum and newly arrived from their freshwater birth streams on their way to four years foraging the subway of salmon, the Gulf of Alaska.

Emboldened by a half-hour successfully paddling around, I decide to essay a tropical-water maneuver, take a deep breath and dive down for a closer look at the sea cucumber conclave. A mighty effort takes my blimp suit and me a foot deep. Everything looks pretty much the same, actually. Staying there proves impossible, so I resurface – into a burning ring of fire.

My face feels like it’s been slapped by stinging nettles soaked in kerosene. What happened? Alien crossfire? I look around.

There’s a lion’s mane floating blithely away. The same creature that figured in one of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes murder mysteries. Luckily, this is a smallish one, less than a foot.

I Teletubby my way to shore, and a guide grins wryly. “Happens.” A vinegar and ammonia solution eases the sting, and soon enough I’m fine, though I smell like a horse stable.

“You might want to shower when you get back to your hotel,” the guide suggests. Good advice. “Aloe cream helps, too.”

An hour later I feel nothing, but have gained a rare tale. How many people have encountered the fabled, notorious lion’s mane while gawking at sea cucumbers? A rare adventure indeed.

Eric is the author of the Michelin guide to Alaska. He lives on a small farm on San Juan Island, where he grows organic hay, garlic, apples and beans. More information on Snorkel Alaska can be found at snorkelalaska.com. x