One of Grant Gunderson’s favorite photos, the only exposure captured during a break in the weather on the Shuksan Arm.[/caption]

One of Grant Gunderson’s favorite photos, the only exposure captured during a break in the weather on the Shuksan Arm.[/caption] For more than 15 years, Bellingham-based photographer Grant Gunderson has shot for ski publications around the world and exposed skiers to destinations ranging from Japan to the Mt. Baker Ski Area.

He grew up in Yakima, skiing at White Pass, and wrangled his love of skiing and photographing his friends into a dream career while still in college at Western Washington University, studying plastics engineering. Recently turned 40, and with a two-year-old son, Gunderson reflects on his time behind the lens.

Mount Baker Experience: What’s a typical winter like for you?

Grant Gunderson: I think the biggest thing I try to do is follow the snow. Every year it’s a bit different, but generally I try to be around Baker early season. I try to go to Japan in January. I like to be back around Baker for February and March – hopefully, the rest of the season. If it warms up here and starts raining, I try to go to B.C.

That’s probably the one thing that’s changed the most for me in the last four or five years. I used to be able to go out all winter long with no set schedule, no plans, no contracts, no obligations, nothing. Just go and create great ski imagery, hopefully. And I would sell enough at the end of the year to pay for all the money I spent during the season and hopefully make a little profit. Those days are gone.

Why is that?

The entire industry changed. No one’s really buying stock images any more so it’s all preset contract work. And magazines definitely aren’t what they used to be, which is kind of sad.

So the balance of editorial vs. commercial work has changed a lot for you?

It’s had to. Ten years ago I could survive solely off print. When I would sell an ad or whatever I was super happy because it was a nice little bonus. But yeah, those days are gone.

What has that change been like for you?

I think it’s more challenging now. Before, I’d set my own schedule and if it looked like it was going to snow three feet in B.C., I'd drive up last minute and be there for the storm. Now I have a lot of fixed dates when I have to be places. And even if I show up and conditions are horrible, I have to make it look good. That’s not always easy.

I think now that the dust has settled, it’s actually better for me. It’s easier to pay my mortgage. I know I’m going to get paid at the end of the year and I don’t have a huge credit card bill at the end of the season.

Who do you do contract work for?

A lot of tourism. I have a pretty good contract with the Japanese government to promote skiing in Japan. I do a lot of work for tourism agencies all over the place now. Most of them want me to create imagery that gets people excited to go there – make Japan look like the enticing powder mecca that it is, for example.

I think the one thing that’s stayed consistent for my entire career is, I always thought when I started out that as long as I can create good photos that make people excited to go spend time in the mountains, I’d be successful and it would work itself out. And that’s still true.

Adam Ü in Myoko, Japan. Gunderson’s photography helped make Japan a ski destination. He says he’ll go back every year.[/caption]

Adam Ü in Myoko, Japan. Gunderson’s photography helped make Japan a ski destination. He says he’ll go back every year.[/caption] Why is that your goal – to get people excited to go to the mountains?

It’s something I have always loved to do. From a pretty early age I felt like my purpose on this planet is to get people excited to spend time in the mountains. I feel like I've been really lucky to figure that calling out for myself.

Does doing more commercial work make it harder for you to be fulfilled as a photographer?

It’s different. It used to be all about going out and creating a handful of the absolute best images I could come up with, try to do something completely unique and different. It was more quality over anything, so if I went out and got one really amazing shot, I was happy. Now it’s quantity. It has to be high quality, but I have to produce a lot more than I used to. When I do get that really amazing shot, it’s even more rewarding now.

The schedule of a ski photographer in the social media age makes it harder to capture more time-consuming photos like this one, of Dave Treadway skiing at Monashee Powder Cats in 2013.

The schedule of a ski photographer in the social media age makes it harder to capture more time-consuming photos like this one, of Dave Treadway skiing at Monashee Powder Cats in 2013.Social media has played a big role in that shift. What do you think about it?

I have a love-hate relationship with it. I’m probably way less into social media than people would think. The truth of the matter is, I only really post on social media because I have to for work. I’d prefer to totally be off it.

With social media I kind of feel like everything got diluted. Everybody is now a media producer; anyone with a cell phone is going to be posting ski photos now.

And a lot of them are really good.

They are. It’s pretty cool. But there’s no filter, so stuff tends to get lost in the mix unless it’s really spectacular. The sheer amount of amazing stuff you scroll by and never see again is crazy when you think about the way it used to be with print, where you’d look at the same magazine all year long. You get on Instagram and scroll through 100 photos, can you remember a single one?

It has got to that point where my social media following has a lot to do with what I can charge. For the athletes, what they get paid for on a lot of projects is totally based on their follower count. I know people who have gone out and bought a huge follower account because that’s how the sponsors decide to pay them now. Does that mean those followers are worth anything?

I think the industry needs to figure out what the right balance is. At some point, the social media stuff is going to get pulled back and people are going to realize that it’s not all it’s cracked up to be. If you’re a ski brand and you put everything on Instagram, I don’t know if you’re really getting the return on investment you think you’re getting.

Is there anything you say to upcoming photographers?

I would say it’s definitely not easy to make a living doing what I’m doing and I think it’s more difficult now to break into it than it ever has been, which is sad. On one hand, it’s easier access than it ever has been for someone starting out. It’s a lot easier to build a big following with social media. But how do they monetize that?

Shooting skiing means you spend a lot of time in avalanche terrain. How do you manage that?

Something I really want to stress is, if conditions are dangerous, I’m not looking to push it at all. I’m probably more conservative now than I ever have been. We’re way more proactive with it than we were 20 years ago. We know more. But you know, in the last 20 years, I’ve lost more friends to the mountains than most people have to begin with and I don’t want to lose any more.

On one hand, I feel a little guilty about it because we’re producing imagery that gets people excited to go spend time in the mountains and ski, go find a powder stash outside the resort. But what people don’t see when they see a photo is the entire safety apparatus behind the scenes.

I think people are taking close proximity to the ski area for granted these days. Back in the day we might not have been as on top of snow science as we are now, but we had unwritten rules. When I showed up at Mt. Baker, all the old-timers were like, “We’re not going to go out until at least 24 hours after it stops snowing. We want to let it settle and stabilize.” That was pretty smart. Now, during the storm people are going out and pushing it.

George Dobis, who used to own Mt. Baker Snowboard Shop, gave me the best advice I think I’ve ever gotten about the mountains. “You start your life off in the mountains with a handful of luck, and you hope you have a handful of knowledge before it’s gone.”

Cole Richardson goes big at Mt. Baker in 2019.

Cole Richardson goes big at Mt. Baker in 2019.Have you taken flak for being in close calls with avalanches in the past?

Oh, for sure. Nobody’s perfect. You’re going to make a mistake no matter what at some point. There’s no way around that. If you have a close call, that’s a good learning experience and the best thing you can do is tell people so they can learn from your mistakes.

That’s why it’s really important to make sure you’re as prepared as you can possibly be and stack all the odds in your favor; you always have avalanche gear, you’re checking your beacon at the parking lot, you’re actually practicing using your beacon, you’re practicing rescues and have good communication tools like radios, so if something does go wrong, you’re able to deal with it.

I lost three friends in an avalanche at Stevens Pass. Right after it happened, I told myself, you know what, I don’t care how much it costs, I’m buying professional-grade radios. And I know the athletes don’t have the money to do it so I’m going to buy six of them so no matter what crew I’m with, I’ll just take care of the radios.

I have all the ski patrol frequencies so if there’s an accident at the ski area I can talk to them right away. In B.C. we do a lot of backcountry skiing. I have every single helicopter frequency for the entire province. If there’s an accident, chances are – there’s so much mechanized skiing – I can pick somebody up right away. That’s the behind the scenes stuff people don’t see or understand.

How do you keep photography interesting?

Anytime I take a photo, I’m always looking for a way to do it better, how to do it differently and come up with new ideas. It's really easy to fall into a rut and start doing the same stuff over and over.

But what keeps it fun and interesting for me is, I’ve gone out and shot certain runs on Baker probably 1,000 times at this point and every single time it’s completely different – the snow comes in different, the wind’s different. Yeah, it may be the same location, but it’s always something new and it doesn’t get boring that way.

I believe a lot of it is because I get to spend so much time in the mountains. Because of that I think the way I’ve looked at it has evolved. I see a bigger picture. It’s not just the action; it's the lifestyle, the culture, the nature. And I found that people get really excited about that stuff.

How has having a son affected your work?

The biggest thing for me is, especially now that I can take him out and do stuff with him, I have as much fun taking him biking or skiing as I do if I go out with my friends. It’s really, really enjoyable and I think it’s actually helped me a lot, because the stuff I’m seeing him pick up on and get super excited about, it’s a lot of small details you and I probably totally gloss over. So it’s given me a lot of ideas on how to capture some of that stuff.

Gunderson mountain biking with his son in Bellingham.

Gunderson mountain biking with his son in Bellingham.What was it like branching out from just shooting skiing?

I didn’t shoot anything besides it for a really long time. I think branching out has allowed me to refine my photography skills. With mountain biking I use a completely different set of techniques than I do with skiing. Now, every once in a while I'll shoot skiing in a totally different way than I ever had before, because I've been exposed to something through mountain biking, hiking or whatever. It keeps me sharper.

Skiing has always been my first and foremost passion. Mountain biking has always been a very close second. It’s almost exceeded it sometimes. And I was really hesitant about turning another one of my hobbies into work.

For the longest time I wanted to keep mountain biking totally separate – just for myself. I kind of changed my mind with it a little bit. I was like, you know what, I really like mountain biking in Bellingham but I’m going to go check out some other spots. If I can shoot just enough mountain biking to pay for the cost to do it, that’s a good mix.

With skiing I go a lot of places that I have to. With mountain biking, I'll set up a trip to a place I want to go first and foremost, and then I’ll reach out to the tourism agency or whoever else might want to support that.

Carston Oliver, Kersten Koegler and Brice Shirbach mountain biking in Zermatt, Switzerland.

Carston Oliver, Kersten Koegler and Brice Shirbach mountain biking in Zermatt, Switzerland.Do you have a favorite photo from your career?

I think one of my favorites is a black and white ski touring shot of Shuksan Arm. I think the reason it’s one of my favorites is I did literally nothing on it besides convert to black and white. We were skiing pow all day, it was storming, I met three buddies when they got off work at ski patrol. When everything was getting shut down for the day, we decided to go for a ski tour. The frame before it’s snowing. All the sudden the light was epic. I didn’t try to set anything up, we were just breaking trail going up the Arm. I took the one photo, skied down and it was snowing again. It was as pure as you could possibly get.

You broke your ankle early last December. How did that impact your ski season and the rest of your year?

I ended up skiing 40 days. If I actually knew that I had broken as many bones and done as much damage to my ankle as I did, I probably wouldn’t have skied at all. Every time I went to the doctor last winter, they’d find another fracture, so it was kind of a painful winter.

Are you recovered now?

I’d say like 90 percent.

What did that do to your career?

I was able to get out just enough to cover most of the contracts. And then the ones that I couldn’t really fulfill, I’ve done some mountain bike shoots and stuff to make up for it. It was definitely a scary situation financially.

How did you get out to fulfill those contracts?

A spoonful of concrete. I just kind of made it happen. Luckily, all the fractures were confined to my ankle, and a ski boot is kind of like a cast. So I was able to limp around a little bit, but I definitely couldn’t ski like I normally would.

What are your plans for this winter?

Ski as much pow as I can to make up for missing it all last year. I think I’m hungrier to have more free ski days this year than I’ve had in a long time because I didn’t get a single one last year. But literally, it was so painful for me to put a ski boot on.

I guess that’s the one time this actually felt like a job. That made me more appreciative of the career I've built for myself than anything. I think maybe I started to take it for granted a little bit. I was getting a little jaded by it. Being stuck on the couch, knowing it’s a sick day to go skiing, and not being able to physically go do it … I was like, you know what? I’m lucky.

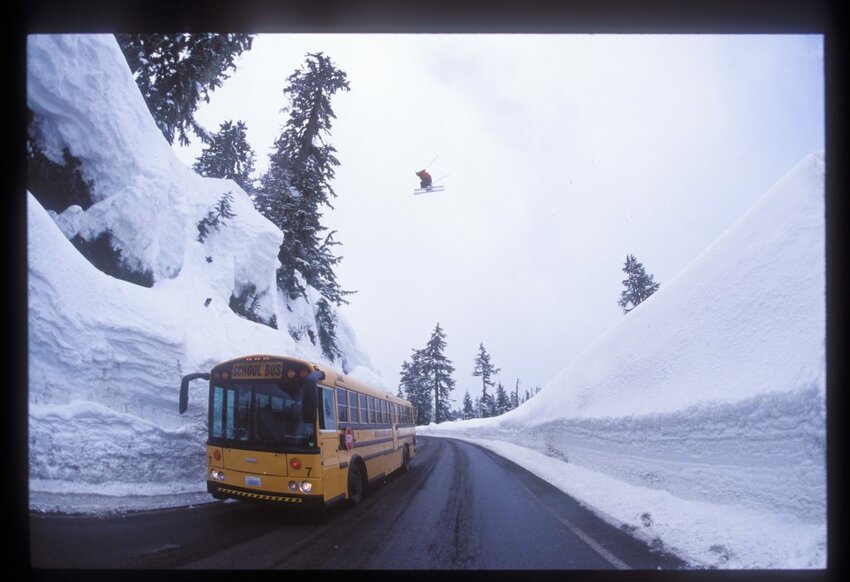

From the archives: James Heim jumps the road gap at Mt. Baker on film in the early 2000s.

From the archives: James Heim jumps the road gap at Mt. Baker on film in the early 2000s. This 2008 photo of Bryce Phillips in the Alta backcountry landed on Skiing magazine’s cover and earned Gunderson a lot of attention.[/caption]

This 2008 photo of Bryce Phillips in the Alta backcountry landed on Skiing magazine’s cover and earned Gunderson a lot of attention.[/caption]