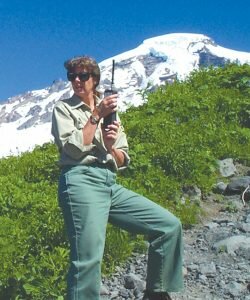

A hiker on the north side of Mt. Baker. Photo by Jefferson Morriss.

A hiker on the north side of Mt. Baker. Photo by Jefferson Morriss.As the snow melts on Mt. Baker, hikers, climbers and campers head to the hills. Roads clear of debris, trails dry and snow consolidates to create easier passage on climbing routes. Behind the scenes of the summer recreation boom, folks prepare for a busy season of work on the mountain. Trail crews carry McLeods and Pulaskis uphill to remedy the winter’s ravages, guides prepare aspiring mountaineers for summit attempts and researchers scout data collection sites. Within each industry on Mt. Baker, there are women working every day to protect natural resources and make mountain recreation possible. They haul in gear, pack out trash and are fueled by their passion for the outdoors and this region. Here is a peek into a few of their stories.

Barb RicheyMt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest

Barb RicheyMt. Baker-Snoqualmie National ForestAs the wilderness and trails manager for the U.S. Forest Service’s Mt. Baker Ranger District, Barb Richey has managed the Mt. Baker Wilderness since it was designated as “wilderness” in 1984. Before every summer, Barb prepares her crews with the training and supplies they need to do their jobs safely. She oversees the climbing ranger program, a two-person team that assesses route conditions, provides information to the public and makes sure climbers take care of the mountain. Barb also manages trail maintenance crews and a volunteer education program called Mountain Stewards.

“We’re all public servants,” she said. “We’re all there to try to open the trails and manage the land so it’s available and accessible for the public to enjoy.”

While Barb spends less time working outside in her current role, she is no stranger to fieldwork. She began as a backcountry ranger in 1980, when the north side of Baker was known as the Glacier Ranger District. It took a few tries for her to land a position with the Forest Service; the first time she applied she was told, “It’s not a place for a girl like you. It’s dirty work.” Barb persisted and has since served as a backcountry ranger, firefighter, educator, trail crew worker, and finally as the wilderness and trail manager.

the first time she applied she was told, “It’s not a place for a girl like you. It’s dirty work.”

Barb’s advice for women seeking careers outside:

“Go for it! Take every opportunity to knock on doors and find your way in! You get turned down once, go and knock on a different door, because maybe that door will open for you.”

Barb’s favorite spots on Mt. Baker:

“I hold dear all those places that I went with my kids: Skyline, Chain Lakes, Ptarmigan, Yellow Aster Butte, Heliotrope, Heather Meadows. It’s really unique that we have this in our backyard, and so accessible.”

Barb’s message to recreationalists:

“It’s great to see people out, and the more education and information we can provide to people on how to take care of the resource and be responsible out there when they are recreating, the less the agency has to do to crack down and manage it. They do have to pack out their poop now! That’s a requirement for Mt. Baker.”

A native of Bellingham, Katlynne grew up in the shadow of Mt. Baker. She now spends her summers leading new mountaineers to its summit as a guide for the American Alpine Institute (AAI). Most of her season is spent in the Cascades guiding alpine objectives and teaching climbing skills. She also guides on Denali and oversees Denali expedition logistics as the Institute’s Alaska coordinator. As a guide, Katlynne seeks to empower people to take on new challenges and manage their vulnerabilities when at their limits in the mountains.

Katlynne is motivated to expand AAI’s women’s programs: “Even though women have been in the outdoors and have been climbing for a while now, there’s still a lot of firsts,” she said. She sees opportunity to develop women-specific courses that don’t currently exist anywhere.

Katlynne’s path to Baker’s summit began with a trip up another Cascade volcano. She began guiding climbs of Mt. St. Helens in 2011, then followed her passion for leading people in the outdoors to a job with Colorado Outward Bound School. After falling in love with technical rock climbing, she started guiding with AAI in 2017.

Managing her seasonal lifestyle is not always glamorous. “I don’t remember the last time I spent Christmas with my family,” she said. Summer and winter are her busiest seasons; fall and spring are transitional and she has more time to slow down, spend time with family and friends, and squeeze in some personal climbing.

Katlynne’s advice for women learning how to climb:

“Get outside and see what the terrain looks like. If you can get your eyes on something, you have a better understanding of what it might take. Seeing it is the first step in being able to visualize yourself out there doing it.”

Katlynne’s favorite spot on Mt. Baker:

The Black Butte camp – “You can see everything!” she said. “You can see the Olympics, the Twin Sisters, all the way up to the Canadian Coastal Range.”

Katlynne’s least favorite part about fieldwork:

“Dealing with other people’s poop. About once a year I have a tragic human poop story.”

During the last few summers, Barbara Budd spent nearly every weekend on Mt. Baker’s trails. She isn’t just a die-hard hiker though; Barbara is the Northwest regional trails coordinator for Washington Trails Association (WTA). She leads volunteer trail crews, getting a ton of trail maintenance done while practicing the WTA’s motto of “safety first, fun second and work third.” She works closely with land managers to prioritize projects, meeting a couple times a year with representatives from Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest. Barbara loves the energy and enthusiasm of volunteers and is motivated by helping people learn new things about trail work and living in the outdoors.

While her projects vary with the seasons, Barbara works outside in Washington year-round. As the snow melts from the alpine, her crews head higher, working in the Mt. Baker region and Lookout Mountain area. During the winter, she leads volunteers in the lowlands, working on the San Juan Islands, at city parks in Mount Vernon and Bellingham, and at county parks in Skagit and Whatcom counties.

There are opportunities to get involved with the WTA all over Washington and Barbara is particularly excited about WTA’s efforts to make trail work more welcoming to folks who might not otherwise try it. WTA works hard to “educate all people who volunteer with us that everyone can do trail work, as opposed to what we've been told to believe,” she said.

The most challenging part of Barbara’s

fieldwork:

“We work in pretty much all weather, unless the ground is frozen, or there are high winds or bad smoke. Keeping volunteers happy, motivated and cheerful while it is 40 degrees and raining is a challenge!”

Barbara’s favorite spot on Mt. Baker:

The first time she visited Mt. Baker, Barbara camped on the south side of the mountain at Mazama Park below Park Butte. She recalls thinking how beautiful and remarkable the view of the Easton Glacier is from that spot.

Barbara’s message to recreationalists:

Don’t cut switchbacks; it causes erosion. Pay attention to the toilet situation. Learn how to poop in the woods. Learn about when and where it is appropriate to have fires. File trip reports with WTA; land managers are paying attention to these, so reports from hikers play a role in taking care of the trails.

Last summer, Elizabeth spent over 20 days on the south side of Mt. Baker, gathering data to test a new method of measuring glacial change. Traditional glacier monitoring methods require researchers to drill long poles called ablation stakes into the ice at different elevations. Researchers then return to collect measurements from these points throughout the season. Elizabeth collected data from the Easton Glacier using this standard method and is comparing her results with a new, more efficient method that uses drone imagery.

In addition to slogging uphill on snow many times to check her ablation stakes, she teamed up with David Shean from the University of Washington, who flew drones to collect repeat overlapping photos of the glacier. This new method allows Elizabeth to compare drone imagery taken in May with images taken in September to calculate how much the surface of the glacier changed over the course of a season, with accuracy down to the centimeter. Elizabeth’s research was a team effort, with a diverse crew of skiers, climbers and guides joining her rope team as she visited her ablation stakes throughout the season.

She ended up in Bellingham as a graduate student at WWU after completing an undergraduate degree in geology at Carleton College and teaching field science in Wyoming at the Teton Science Schools. Elizabeth was motivated to study glaciers because of their critical role as freshwater reservoirs, and part of her research examines how glacial change affects streams and rivers formed by glacial runoff. She hopes that this new, more efficient technology will make it possible to monitor more glaciers throughout the world.

How Elizabeth’s summer season compares with winter:

“Summer is spent in the field, on the ground, collecting data. Winter is sitting in the computer lab, staring at GIS, running into dead ends, reading scientific papers – the least glamorous part of my project.” As an avid skier, Elizabeth manages to get outside in the winter, even though she isn’t collecting data.

Elizabeth’s favorite parts of this region:

She loves having the ability to ski on a volcano in the morning, go for a bike ride in the foothills in the afternoon, then spend the evening at the coast. “It’s the coolest,” she said. “There are so many different ecosystems so close together.”

Elizabeth’s go-to meal in the field:

Most of Elizabeth’s dinners in the field consist of Annie’s macaroni and cheese with arugula. After long trips collecting data, she always makes a stop to the Mestizo Mexican Family Restaurant in Sedro-Woolley for a super burrito.