From Mt. Olympus in 2018.

From Mt. Olympus in 2018.The knowledge of a mountain, the true understanding of where it is rooted in the earth is not found in a line to the top. Visit one of the great trees of the world and almost every person will walk all the way around it, stare high into the branches and wonder at its aged bark and healed over scars. So too does the mountain inspire all to see its many facets and every side.

For this reason, The Circumnavigation Project was born.

Among Washington state’s Volcanic Court are five great volcanoes, the titans of the Cascades: Mt. Rainier, Mt. Adams, Mt. Baker, Glacier Peak and Mt. St. Helens. Where each volcano can be viewed as representing a portion of Washington state’s mountainous regions, there’s a hole in that logic. On the northwestern peninsula, estranged from the greater 700-mile Cascadian chain and lacking any volcanoes are the Olympic Mountains. Where it doesn’t come up short is in moss and glaciers; they are found in equal amounts among a sea of primordial forests and serrated peaks. Towering above this kingdom of green is its Titan, Mt. Olympus. While it may not blow its top every hundred or a thousand years, it is a companion in spirit, if not in nature. For this reason, I added it to my circumnavigation project, making six peaks in all.

The Circumnavigation Project

Mt. Adams (12,276') Circumnavigation, June 13-15, 2008

Glacier Peak (10,541') Circumnavigation, June 22-28, 2017

Mt. St. Helens (8,364') Circumnavigation, March 12, 2018

Mt. Rainier (14,410') Circumnavigation, April 23-25, 2018

Mt. Olympus (7,980') Circumnavigation, May 25-June 1, 2018

Mt. Baker (10,781') Circumnavigation, July 16-18, 2022

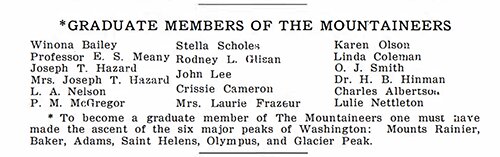

One of the early mountaineering groups in the Pacific Northwest, established in 1906, is The Mountaineers. Similar groups like the Oregon Alpine Club, Cascadians, Sherpas, Mazamas and others set off a boom in mountaineering in the early 1900s. For The Mountaineers part, where it relates to my project, they had a pin they’d present to the mountaineers who had accomplished what they called the Big 6. Its objective was ascents of the aforementioned peaks, all on club-sponsored trips (not independent climbs).

Photograph by J. O. Boen from the 1891 ascent of the Boulder Glacier, and the first ascent by a woman (3rd known ascent). You can see Sue right of center, and camp to the left. Three others can be seen in the background. This is the second time a photographer was on Mt. Baker (the first a few months earlier on the Coleman Glacier).

Photograph by J. O. Boen from the 1891 ascent of the Boulder Glacier, and the first ascent by a woman (3rd known ascent). You can see Sue right of center, and camp to the left. Three others can be seen in the background. This is the second time a photographer was on Mt. Baker (the first a few months earlier on the Coleman Glacier).When it comes to just the five volcanoes, Charles E. Forsyth is the earliest known person to complete ascents of each, finishing in 1910. When it comes to Washington’s six major peaks, a woman, Helen Winona Bailey (1873-1938), accomplished this feat in 1917. So far as can be proven, she is the earliest to do so. Skip forward to 1921, and The Mountaineers write that there are 17 graduates who received the six-peaker pin, eight of whom were women.

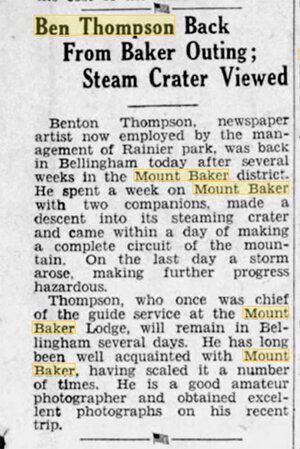

As far as ski circumnavigations go, such as I was contemplating, the history is primarily relegated to the last 50 years. There’s one exception, though. Another early Mountaineer club member, Ben (Benton) Thompson, along with Don Henry and Darroch Crookes, attempted a ski circumnavigation of Mt. Baker in 1932. As told in the 1941 Mountaineers Annual, they went from Mt. Baker Lodge and “... traveled past Camp Kizer the first day and camped that night at the junction of the Mazama and Rainbow glaciers. Next day it was snowing a little and the weather looked bad, but in spite of this they made the summit of the peak and camped that night in the crater, making good use of one of the fumaroles for cooking dinner ... from the cabin (Kulshan) they camped on Thunder Glacier, having had some wonderful spring skiing snow, and the second night was spent near Easton Glacier. Next day they anticipated making the rest of the trip to Mount Baker Lodge, a long distance involving the crossing of the Easton, Boulder, Park and Rainbow glaciers. A sudden violent thunder and lightning storm defeated this project and drove them down to timber on the south side of the mountain, from whence they reached civilization again by way of the Nooksack River.”

As far as ski circumnavigations go, such as I was contemplating, the history is primarily relegated to the last 50 years. There’s one exception, though. Another early Mountaineer club member, Ben (Benton) Thompson, along with Don Henry and Darroch Crookes, attempted a ski circumnavigation of Mt. Baker in 1932. As told in the 1941 Mountaineers Annual, they went from Mt. Baker Lodge and “... traveled past Camp Kizer the first day and camped that night at the junction of the Mazama and Rainbow glaciers. Next day it was snowing a little and the weather looked bad, but in spite of this they made the summit of the peak and camped that night in the crater, making good use of one of the fumaroles for cooking dinner ... from the cabin (Kulshan) they camped on Thunder Glacier, having had some wonderful spring skiing snow, and the second night was spent near Easton Glacier. Next day they anticipated making the rest of the trip to Mount Baker Lodge, a long distance involving the crossing of the Easton, Boulder, Park and Rainbow glaciers. A sudden violent thunder and lightning storm defeated this project and drove them down to timber on the south side of the mountain, from whence they reached civilization again by way of the Nooksack River.”

It wouldn’t be until 2003 that the first known and complete ski circuit of Mt. Baker would take place. Ski circumnavigations of the others were first completed on St. Helens in 1984, Rainier in 1986, Adams in 2008, Glacier Peak in 2017 and Olympus in 2018, as Alpenglow.org reports. I headed out for Baker in the middle of 2022.

July 16, 2022: Scott Paul Trail to Squak Glacier

Present means now and gift. It’s easy to forget that. Easy to lose track of the now. But now is a gift ready to be unwrapped over and again, countless times in a life. This is why after spending most of a month laid up with Covid-19 for the first time, I was ecstatic to get outdoors with just the moment, the mountain and me.

As I drove north on Interstate 5, my self-prescribed cure to my woes of traffic were views of Mt. Baker. Rain clouds dominated and submerged its snowy mantle from view. I was reminded of my first attempt to circumnavigate Mt. Baker with Colton Jacobs. Icy snow and a night of wind failed to inspire, weather shenanigans that seemed destined to repeat on this go around.

A day later I sat in my RV with my eyes burrowing into the gray wall. Rain slapped my windshield, adding a pathetic drumroll to my arrival. An updated forecast I’d loaded before going out of coverage harmonized my mood. So appropriate that this would happen. A season of weather rollercoasters that rivaled any I’d endured in my life. Good weather slips out of reach with every update.

A day later I sat in my RV with my eyes burrowing into the gray wall. Rain slapped my windshield, adding a pathetic drumroll to my arrival. An updated forecast I’d loaded before going out of coverage harmonized my mood. So appropriate that this would happen. A season of weather rollercoasters that rivaled any I’d endured in my life. Good weather slips out of reach with every update.

As a teenager I remember looking at forecasts in the local paper. Their dependence was laughable as far as mountains were concerned. The rule then: Go and see. A light raincoat was exchanged for a heavy one, a grimace for a smile and hesitation for choice.

Onboard the Jason Hummel Express, my pack and I ground our way up the Scott Paul Trail, Covid lungs howling and spittle flying. Mountains and molehills, it’s all perspective.

I was entertained by the surreal green of the surrounding foliage until it was folded under white snow (~4,500'). Mother Nature exchanged a few clouds for blue sky, an investment I was all for. Timing is everything, and so I pitched my tent in a volcanic field. Like fresh water, the skier should never bypass a dry camp if they can avoid it.

From Mt. Baker in 2022.

From Mt. Baker in 2022.The remaining hour or two before dark was spent watching light dance on the Squak Glacier. These icy harbingers of winters’ past are my muse, so to speak. Their history and tales are fascinating to me. When Edmund T. Coleman (1824-1892) and party ascended Mt. Baker in 1868, Coleman wrote, “The day passed by, and we were anxiously concerned in regard to Squock and Talum; but they returned late in the evening, and reported that they had reached a spot above the snow line by a path that was comparatively easy to find. They brought in a couple of marmots, which they demolished at supper.”

Both glaciers, as far as I can ascertain, were named in the early 1970s by Austin Post, a glaciologist and aerial photographer. He did so to commemorate the two native guides that made Coleman’s ascent possible.

Frothing clouds churned up from the green valleys and washed over me that evening. In a second, my universe shrank to my tent and surrounding rocks. Then, as sleep gripped me, my world shrank to nothing.

Frothing clouds churned up from the green valleys and washed over me that evening. In a second, my universe shrank to my tent and surrounding rocks. Then, as sleep gripped me, my world shrank to nothing.

July 16, 2022: Squak Glacier to Roosevelt and Rainbow Glacier Col

I left camp around 10:30 a.m. Only by then had the rain let up and the clouds peeled open enough for me to see. I’d considered making one long day out of this mission, returning to camp, but the weather forced my hand. Being solo, I lean toward being as conservative and flexible. With my big pack and all my gear, I left people and any easy retreat behind.

Mt. Shuksan from Mt. Baker in 2022.

Mt. Shuksan from Mt. Baker in 2022.Before long, I reached Crag View and descended Talum Glacier to a spine of rocks. I crossed at 6,000 feet and skied onto the Boulder Glacier, whose sight never fails to impress me. Like the Avalanche Glacier on Mt. Adams, the Boulder Glacier has irregular, but historically frequent avalanches of a catastrophic nature that scour the mountain every two to 10 years. Fumaroles in the Sherman Crater destabilize the snowpack. Also impressive is the sheer amount of crevasses. Like the Emmons Glacier on Mt. Rainier, it is riddled with them.

At the Boulder Park Cleaver, I stopped and pondered its first ascent in 1891, a climb made by Susan L. Nevin Ewing (1870-1914) and party. I’ve included a portion of Ewing’s words from a September 2, 1891 News Tribune article below, as well as a photograph of the group taken by her brother in law, James Orville Booen (1864-1934). Unlike much of the world beyond where this photo was taken, little has changed in this terrain in 131 years since their visit.

What other views I may have had turned myopic. Clouds wrapped around me, cloying me in a heavy wet that began to ease only as I reached the far end of the Park Glacier. Along my way, sightless, I often arrived at a crevasse only to chase it up or down one end or another, like some blind mouse in a maze.

Lowhung clouds rolled off the sea and crashed against the mountains.

With copious amounts of side stepping, and a short boot pack, I skied to the col between Roosevelt and Mazama Glaciers. In a rockfield I discovered a dry camp, and none too soon. Between squalls of rain, the mountain presented itself for exactly two minutes. With no time but the present, I ran around, a wildman leaping from boulders to snow trying to catch every angle and shift of light and mood.

From Mt. Olympus in 2018.

From Mt. Olympus in 2018.Photographs and poetry say a lot with a little. I waited for inspiration because mountain time is much preferred to sleeping, even when rain refuses to let up. You can watch Mother Nature curl up the clouds, puff out flames of red and yellow, and fire ballistae of shooting stars — but for waking eyes only. None of this was for me, not on this night. Rain was cast down from the heavens, thunder rattled my ears and lightning speared my hopes of better weather in the morning. Silently dreams overshadowed all my worries.

July 17, 2022: Rainbow/Roosevelt Col to trailhead

Come morning, I opened the tent and awoke to my earlier dreams made reality: Blue skies and sun. Low clouds once again hung over the valleys. Above me stark white clouds called lenticulars flowed over the summit, so perfect they seemed fake. With camera in hand, I was lost for hours. What is the parable? When there’s nothing to do, there’s everything to gain?

Eventually I rounded up my things and turned skis downslope. I glided halfway across the Coleman Glacier and then climbed to Colfax Saddle (~9,000'). A road washout blocked people from the Coleman–Deming route. As such I was left alone with 359 degrees of the mountain to myself.

My skis ran across the Easton Glacier and flew over cracks, and my mind ran over the previous trips I’d taken as part of The Circumnavigation Project. So much adventure, so much now, so many gifts that keep on giving even all these years later. Not even the bugs, the boulder hopping down the toe of the glacier nor the sudden shock of dozens of tourists could wipe away my smile. I said hello to everyone, and rolled down the trail like the raindrops I’d spent so much of my time with.

At my RV, beer in hand, I sat on my steps, satisfied. Skiing has allowed me a form of expression, as it has in photography, neither of which I could live without. If all the lines I’d traveled were seen on a map, it’d appear as if a kid scribbled across the paper, but if you stared close enough you’d find that they weren’t scribbles at all, but words and stories too small to make out from afar. x

Jason Hummel is an outdoor adventure photographer based in Gig Harbor. He’s currently working to ski every named glacier in Washington state. Find his stories and imagery at Jasonhummelphotography.com.