The proposed community forest, from Potter Road, on the east side of Stewart Mountain. Ian Haupt photo

The proposed community forest, from Potter Road, on the east side of Stewart Mountain. Ian Haupt photoOn a hazy August day last summer, my field assistants and I meandered our way across the Sholes Glacier on Mt. Baker, where we had spent the previous few weeks asking the glacier questions and finding answers in stakes installed into the ice and in stream sediments. These answers would have cascading, watershed-scale implications — they’d help us understand the impact of glacial retreat on salmon populations and also on late summer streamflow. Our work was organized and funded by one of the communities located downstream of the Sholes Glacier — the Nooksack Indian Tribe.

The filtered late summer sunlight accentuated the ice’s rough and variable texture. Unlike the smooth, blue ice often associated with glaciers, the Sholes Glacier was crisscrossed with ridges and troughs, the result of channel networks formed by substantial summer melt. Occasionally we’d stumble upon a moulin — a gaping hole where the surface meltwater falls away into a bottomless abyss in the glacier.

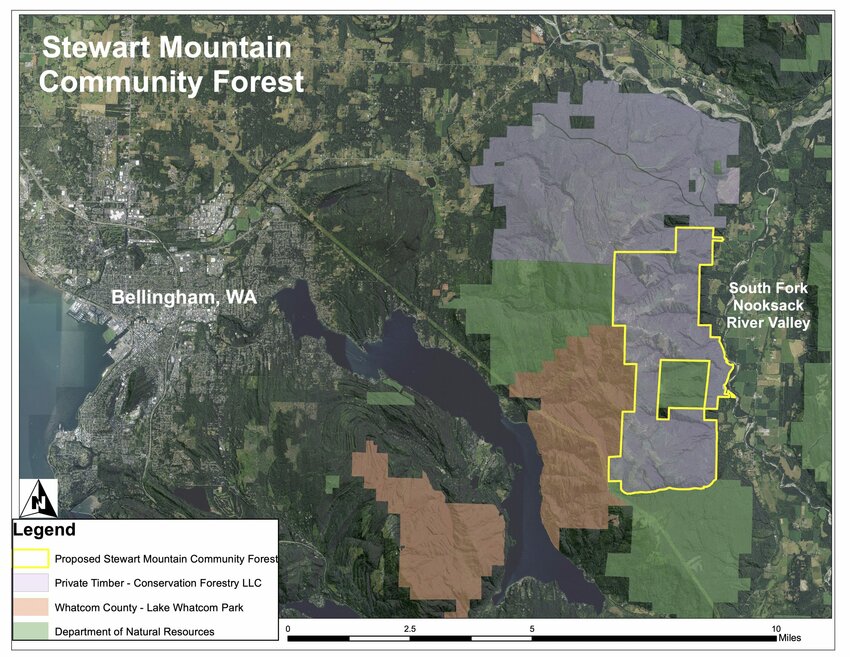

Map courtesy Stewart Mountain Conservation Framework

Map courtesy Stewart Mountain Conservation FrameworkAnyone who caught a glimpse of Mt. Baker from afar last summer likely exclaimed something along the lines of: “I’ve never seen so little snow! The summit is so brown! The glaciers look so sad!” And unfortunately, the data corroborate these roadside visual assessments; some glaciers in the North Cascades lost 8 percent of their mass.

Striking harbingers of our rapidly changing climate, glaciers also provide freshwater for many downstream communities. As they melt, we lose a precious reservoir of freshwater — one that’s especially important in the dry, warm late summer months, when our river systems rely on pulses of cold glacial water to maintain habitable stream temperatures and flows for salmon.

Saving Mt. Baker’s glaciers and increasing its winter snowpack is a largely unattainable goal, at least at the local level. But for Oliver Grah, water resources program manager with the Nooksack Indian Tribe’s Natural and Cultural Resources Department, a simpler solution might exist a bit farther down in the watershed.

“We can’t do anything about the recession of the glaciers and the change in stream flow and temperature due to the receding glaciers,” Grah said. “That’s why we need to take more of a whole watershed approach to promote more stream flow during the summertime to address adequate water for fish and downstream water users, including agriculture.”

The rate at which our glaciers melt is largely out of our control, but the way we manage our forests is not. Such is the inspiration for the Stewart Mountain Community Forest (SMCF) initiative — a collaborative effort to adopt ~6,000 acres of forest on the east side of Stewart Mountain into local ownership.

The project initially hatched in 2014, when staff from the Nooksack Indian Tribe, Whatcom Land Trust, Whatcom County, Evergreen Land Trust, and other informed citizens began meeting to address the health of the South Fork Nooksack River (SFNR) watershed. Two clean water act reports focused on the watershed had just been released and in them, they present the idea of a watershed conservation plan. Bringing these efforts together, the Tribe developed the SFNR Watershed Conservation Plan. All three reports identified the strategy of a community forest to address issues with streamflow, stream temperature, fish habitat and watershed health. More recently, current landowners Stewart Mountain Forest LLC, a timber investment company from New Hampshire, offered to sell a portion of their land on Stewart Mountain to the Whatcom Land Trust (WLT).

Stewart Mountain is located about six miles east of Bellingham nestled between Lake Whatcom and Acme in the SFNR valley.

Clearcuts on the northeast side of Stewart Mountain. Ian Haupt photo

Clearcuts on the northeast side of Stewart Mountain. Ian Haupt photoThe plan was an actionable report aimed to protect and restore water resources and habitat in SFNR Watershed, specifically in the face of climate change. A major piece of the report explored the impact of land management on water resources, namely the relationship between timber harvesting and streamflow in the Nooksack River.

Stewart Mountain, as it stands now, is a patchwork of mature and old-growth Douglas fir stands, young, rapidly regenerating tree stands, and clearcuts. Logging roads wind across the mountain, linking a cobweb of past and future timber harvests. Through the clearcuts are exceptional vantage points of Whatcom County — if you squint, you can almost track a drop of water as it melts off the Sholes Glacier and winds its way down the Nooksack River and into the bay.

Less visible is the complex relationship between the trees, streamflow, frequency of tree harvesting, logging roads and soil. It’s hard to see exactly where a heavily logged forest may have resulted in a landslide. And the warming and decreasing streamflow in the Nooksack River — some product of land management and climate change — is largely invisible to the naked eye.

However, through synthesizing research on timber harvesting and streamflow, Grah and collaborators Susan Dickerson-Lange with Natural Systems Design and Bob Mitchell from Western Washington University illuminate this hidden relationship. In a forest in central Oregon, researchers found that watersheds covered by young regenerating stands of trees resulted in a striking 50 percent reduction of late summer streamflow compared to adjacent watersheds covered by mature and old growth forests. They suggested that higher rates of transpiration (water lost to the atmosphere) from rapidly growing young trees as compared to mature and old growth trees might explain the difference in late summer streamflows. Grah and collaborators were curious if the same trends exist in the SMCF area, where extensive logging since the 1800s has created this mosaic of clear-cut and dense stands of young, regenerating trees. The Tribe contracted Dickerson-Lange and Mitchell to computer simulate the effects of forest management on late summer streamflow in the SFNR watershed. Similar trends emerged from the computer simulations as were observed in Oregon: August streamflow under the existing condition in the SFNR was 27 percent lower than under an assumed natural condition.

The results of this research as applied to forest management pointed toward a tool to mitigate the detrimental downstream impacts of our melting glaciers and diminishing snowpack and the effect of forestry on streamflow. We may not be able to stop Mt. Baker’s glaciers from melting, but we can change the way we manage our forests. Grah calls this a holistic watershed approach.

“To more effectively address reduced streamflows, warmer temperatures and reduced fish habitat, we need to do more than just focus on the river and tributaries — we also need to focus on the upper parts of the watershed as well where commercial forestry is the dominant land use,” he said.

In response to this pilot study, Grah and a coalition of local organizations proposed a promising tool to manage our forests and tackle water resource issues in the SFNR watershed: A community-owned and managed forest.

Not long after the sale offer in 2017, a coalition of the original five entities united to begin drafting a vision for a community-run forest on Stewart Mountain. By acquiring local ownership of the forest, the coalition can manage the forest in a way that considers the health, function and resiliency of the watershed to promote more streamflow in summer.

They plan to shift management of timber harvest to protect on old-growth and mature forest stands, extend harvest rotations to 80 years or more, and implement selective tree harvest as compared to clear-cuts on Stewart Mountain. In doing so, they’ll reduce the acreage of young, regenerating forests that release more water to the atmosphere than mature and old growth stands. Older trees will suck up less water for transpiration than expansive rapidly regenerating stands, and thereby increase streamflow in the Nooksack’s south fork.

Even before the SMCF concept was formalized, the Tribe had already implemented extensive public outreach and stakeholder engagement with the SFNR watershed community while developing their watershed conservation plan. Over the course of seven meetings, they identified a list of priorities related to future watershed management in the watershed. Conveniently, the community forest model will accomplish many of these goals; restoring fish and wildlife habitat, increasing opportunities for tribal members to harvest culturally significant indigenous food, and providing local sustainable forestry jobs.

The community forest will also increase recreation access — the blueprint includes a plan to expand the network of trails for hiking, mountain biking, trail running and horseback riding. The development of the Bay to Baker Trail is also gaining momentum as a result. Once completed, it will connect Bellingham to the Mt. Baker Ski Area via a 74-mile single-track trail.

Where does the project stand today?

The coalition has secured funding to purchase 500 acres on Stewart Mountain and is actively working to secure funding for the remaining 5,500 acres. The core project team has spent the last few months meeting with a broad assemblage of folks involved with timber management, recreation, conservation and more. These conversations are helping to inform their long-term plan for the management of the forest. In addition, they’re working with local forestry experts to produce a plan that balances and meets the goals of both a sustainable working forest and a thriving local timber economy.

“Forests mean a lot of different things to various communities that live in and around them. Here in the Pacific Northwest, communities have a deep-rooted connection to many of these forests. The Stewart Mountain Community Forest initiative is hoping to demonstrate a new way of approaching management of these forests that balances the needs of all these communities,” said Alex Jeffers, conservation manager for the Whatcom Land Trust and a member of the core project team. “Wildlife habitat, forest jobs, recreation, water quality and quantity; we believe that all these priorities can coexist successfully in the same forest.”

Liza Kimberly and her field assistants walk along the Sholes Glacier on Mt. Baker. Amanda Monthei photo

Liza Kimberly and her field assistants walk along the Sholes Glacier on Mt. Baker. Amanda Monthei photoOn that hazy late August day last summer, in shorts and amidst roaring creeks of meltwater, the disappearance of the Sholes Glacier felt all too imminent. We joked about improbable ideas — like glacier blankets to shield the ice from the steamy greenhouse, or painting all of the rocks in its vicinity a bright white to reflect more sunlight.

What we didn’t realize, however, was the ways in which our research could inform a more easily executed solution, just 40 river miles downstream from the terminus of the Sholes Glacier. Knitting glacier blankets and painting landscapes white is lofty, but slight revisions to our land management practices are not. While developing a community forest and logging more sustainably won’t entirely offset many of the harsh consequences of climate change — it certainly won’t save our glaciers — it will provide some relief to the watershed and help us address resource issues related to water supply, water quality and fish habitat. x

When Liza Kimberly isn’t teaching geology at WCC, you can find her seeking alpine powder turns, winding through forests on a bicycle or writing in a notebook and drinking kombucha.