Grizzly bears in Chilcotin, B.C. Jeremy Williams/River Voices photo

Grizzly bears in Chilcotin, B.C. Jeremy Williams/River Voices photoWhen I stumbled, dusted and blistered, from the continuous footpath of the Pacific Crest Trail on a dizzyingly hot day in 2018 and onto a brief slick of asphalt in Southern California, a history lesson was likely low on my To Do list. The fellow I had managed to press into service for a hitch, however, had other plans.

Our destination was the sandwich shops and cooling fans and filtered water of Big Bear Lake, California, a welcome reprieve from the rigors of thru-hiking, when I inquired about the source of the name of the lake. “Used to be grizz, here,” my patron provided. “A lot of grizzlies.”

What followed was a brief history of Big Bear Valley: How one of the first pair of Anglo eyes to behold the high mountain valley had remarked at how “the whole lake and swamp seemed alive with bear.” How grizzlies became a nuisance to the cattlemen that infilled behind the lake and were dispatched with reckless abandon. How the last grizzly in California was seen in Sequoia National Park in 1924, and then never again.

Grizzly bears in Chilcotin, B.C. Jeremy Williams/River Voices photo

Grizzly bears in Chilcotin, B.C. Jeremy Williams/River Voices photoIt seemed distant, now, but oddly pertinent to my own undertaking. My journey north from here would follow the historical retreat of the North American grizzly, and end at the only place they still hung on this far west – the lower 48’s Cascade Range. By now, grizzlies hadn’t been positively identified in the U.S. portion of the North Cascades since 2010, and even that was only a grainy photograph. It was something like chasing a ghost.

If anything, it was something to chew on for the next few months while I walked.

A Resurgence Deferred

The ceremony of a long-overdue office cleanup can bring back plenty.

When Joe Scott, international programs director for Conservation NW and one who has seen the ebb and flow of the grizzly issue across the decades, began to finally deep clean an office that he had inhabited for more than two decades, he was struck by all the people who had been engaged with conservation efforts who have since either dropped dead, retired or outright disappeared.

“It’s been so long, and so many people have worked on this,” Scott said. “The history of it is just long.”

Conservation NW has been the leading voice in an effort to restore grizzly bears to the North Cascades, a crusade they believe will right a longtime wrong in the region and rebalance a delicate ecosystem that for too long has been devoid of the species.

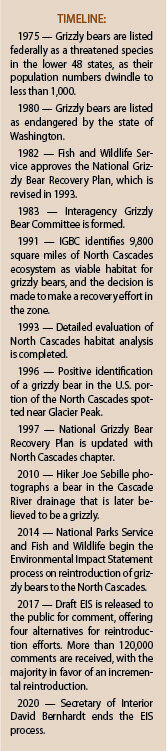

Grizzly bears were listed as federally threatened in 1975. At the time, their numbers in the lower 48 were spitballed at less than 1,000, a far fall from the 50,000 Ursus arctos horribilis that once roamed at their peak, and with the listing clunked into gear a federal process which requires recovering the species to a self-sustaining population.

In the years since 1975, forward momentum has been hard-fought and rarely rewarded. In 1983 the Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee was formed, and in 1993 formalized six different ecosystems suitable for grizzly recovery, including the North Cascades. Then it wasn’t until 2014 when the formal Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) process for the region began, and three years longer until a draft EIS was released to the public for comment. The issue?

In the years since 1975, forward momentum has been hard-fought and rarely rewarded. In 1983 the Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee was formed, and in 1993 formalized six different ecosystems suitable for grizzly recovery, including the North Cascades. Then it wasn’t until 2014 when the formal Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) process for the region began, and three years longer until a draft EIS was released to the public for comment. The issue?

“You could put 10 people in a room from varying backgrounds and they’ll all have different reactions to grizzly bear recovery: From excitement and intrigue and awe to abject fear,” Scott said. Not many other animals evoke the broad range of reactions and emotions, and grizzly bears certainly aren’t the charming poster animals for recovery like fishers or condors or elk.

“They’re victims of the bad stuff,” Scott said.

“You don’t hear about the years and years and the millions of people that interact with thousands of grizzlies in places like Yellowstone or Glacier National Park,” he added. “You just hear about the poor encounters.”

Even still, the overwhelming majority of comments received during the 2017 EIS comment period were supportive of a plan known as Alternative C. An incremental restoration plan, it would introduce five grizzlies every summer for five years to establish an initial population of around 25 bears. At the time, the future had a bit more color in it for grizzlies in the North Cascades. A hurdle that Scott believes the public was able to overcome by embracing the flipside of fear – the awe and reverence that is conferred from seeing an animal of such stature in the wild.

“The fear is subjugated to the excitement and pride of having these animals on our landscape,” Scott said. It is a sharp pull focus that brings perspective to our place in the outdoors, and to how the environment once was before man began shaping it to suit itself.

“Unfortunately, that feeling has not universally translated.”

A Wrench in the Works

Ryan Zinke is a Montanan. One who has seen the coexistence of grizzly bears and ranching and recreation, felt the benefits of having the great bear on the landscape, and upon taking the podium in the headquarters of the North Cascades National Park in March of 2018, must have rather naturally thought: What’s the big deal here?

It was an unlikely position for the then secretary of the interior. During a tenure more often than not beleaguered by environmentalists’ disapproval, Zinke’s lavishing of praise unto the execution of the public process and a firm emphasis of his desire to see the grizzlies be restored to the ecosystem was met with a mixture of skepticism, but also tentative optimism. Zinke ended his time by saying that he had directed the department to expedite the EIS process and issue a decision by the end of the year. It was a conservation win, in most respects.

It wasn’t to last, however, as supporters would find out not two years later, when a new secretary of the interior, David Bernhardt, summarily stopped the EIS process in its tracks. “The Trump administration is committed to being a good neighbor, and the people who live and work in north-central Washington have made their voices clear that they do not want grizzly bears reintroduced into the North Cascades,” Bernhardt said in a press release. The door slammed shut, once again.

Bernhardt undoubtedly had a chorus of voices in his ear, Scott said, including U.S. representative Dan Newhouse (R-Washington) and the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, both representing the voices of ranchers in Washington who felt threatened by an added predator on the landscape. It was Newhouse who, in October of 2019, called a public meeting at the Okanogan County Fairgrounds and let the natural run its course, with local ranchers voicing strong opposition, and the impact of the meeting was another death knell, Scott said.

Faced with such persistent roadblocks, the prospect that grizzlies might ever naturally recover their lost habitat in Washington is unlikely. When a population has dwindled as it has in the North Cascades, where less than 10 remain in an ecosystem of 9,800 square miles, and manmade barriers such as the Trans-Canada Highway largely limit natural migration, a little ‘hand on the scales’ is in order, in the form of what is called an augmentation program. By capturing young grizzlies from healthy populations and grafting them into the ecosystem, the result is nothing short of an ecological jumpstart, bolstering populations in both numbers and genetic diversity that otherwise may have languished.

A grizzly bear. Ana Santos photo

A grizzly bear. Ana Santos photoThe promising news is that this is hardly a novel idea. For nearly three decades, efforts to repatriate a sustaining population of grizzly bears into the Cabinet-Yaak ecosystem of western Montana have largely paid off, with a current population healthily hovering around 50 bears. The success of the Cabinet-Yaak is the blueprint for the North Cascades, Scott said.

“The North Cascades is part of the national strategy to recover grizzly bears in the lower 48, without which the job is not complete,” Scott said. “We can’t have all our grizzly bears eggs in that Rocky Mountain basket.”

A Job Left to be Done

After the Bernhardt decision of 2020, not much has progressed on the North Cascades grizzly front. But with the ushering in of a new administration, Conservation NW and other advocates have a newfound hope.

“There’s a cultural, legal, moral and ethical obligation on the part of public servants and agencies to do this job, which includes the North Cascades,” Scott said. “And Deb Haaland understands the ecological importance of having all native species on the landscape.”

By now, Scott has seen the near and the far history of grizzly recovery in the North Cascades. He has 25 years with Conservation NW, which he joined because they were the only organization that was advocating for grizzly bear recovery in the North Cascades at the time.

“This is near half my freaking life in this thing,” Scott said. “It’s not just me, there’s a lot of people who have put their heart and soul into this effort.”

Conservation NW as an organization is predicated on the concepts of protect and connect, Scott said. They look at conservation from a large-landscape ecologically beneficial level and wonder: What does it mean to have ecological integrity? It means having large enough effective habitat such that all these critters can thrive. For Conservation NW and Scott, the path forward is clear:

“Restart the EIS which was halted by the Trump administration, complete it to a final EIS and record of decision, and follow the science,” Scott said. “That’s what will provide guidance on what needs to happen to recover these bears.”

And for those who still might be apprehensive? “Human beings are the ones with the big brains,” Scott said. “We can coexist with grizzly bears, we just have to have the generosity of spirit to share the landscape with these animals.”

There used to be grizz here. And Scott believes that one day there will be again. x

Based in Bellingham, Nick Belcaster is an adventure journalist who enjoys breaking tree line, carrying as little as necessary and long walks across the country.