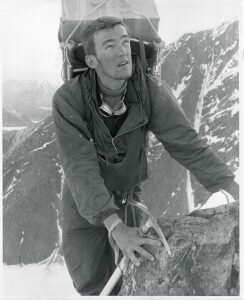

The author on Mt. Rainier in a helmet and other gear used by John Graham in the 1960s. Photo by Kyle Oberkoetter.

The author on Mt. Rainier in a helmet and other gear used by John Graham in the 1960s. Photo by Kyle Oberkoetter.About halfway across the Cowlitz Glacier, one of my crampons fell off for the first time.

It loosened again on Cathedral Gap and then fell off on Ingraham Flats. From the front of our rope team, my guide’s headlamp beam swiveled toward me. “Let’s fix it at the first break,” Steve said.

Even as I dragged the useless metal spikes through the snow, this was one of the most glorious nights of my life. We’d left Camp Muir shortly before 1 a.m., and the 17 climbers in our RMI Expeditions-led group now formed a string of headlamps arcing up Mt. Rainier. It was balmy on the Northwest’s tallest peak. So warm that our guides told us we could leave extra water bottles outside the bunkhouse overnight – there was no risk of freezing. On the Ingraham Flats, moonlight glowed just bright enough to reveal the sharp outline of Little Tahoma, a promise of what the Cascades might look like, once awash in full sun, from more than two miles above sea level.

At 11,200 feet, I sat on my pack, refueling the best I could with gummy worms and palmfuls of peanuts, raisins and M&Ms. Steve crouched in front of me, clutching my crampon. A simple tightening should fix the problem. Then he looked up. “It’s a goddamn screw.”

Of course, he couldn’t have been all that surprised. Three days prior, the trip began with a gear check, everyone splaying their equipment across the lawn at the RMI compound in Ashford. The guides needed to examine everything, from head to toe, starting with helmets. While other climbers displayed sleek, polycarbonate shells that didn’t stick out much farther than the circumference of their heads, I held up an orange plastic helmet, which might as well be an overturned fruit bowl with some Styrofoam and a chinstrap. One of the climbers in my group likened it to something you’d see in the North Korean military. Steve did a double take. I told him the helmet belonged to my wife’s grandfather, who’d done all sorts of serious mountaineering in his day. Steve turned it over, tugged on the chinstrap. He said he’d need to think about it.

Soon, we came to the harnesses. Mine, like my helmet, required extra scrutiny. “You know the shelf life of a harness is typically 10 years?” Steve said.

I didn’t know that. I’m not a mountaineer. Not like my wife’s grandfather John Graham, who long ago summited Denali wearing this harness. He’d gone up the center of the North

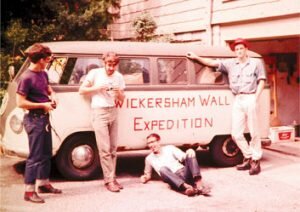

The author’s grandfather-in-law, John Graham, on the first ascent of Denali’s Wickersham Wall in 1963. Photo courtesy of John Graham.[/caption]

The author’s grandfather-in-law, John Graham, on the first ascent of Denali’s Wickersham Wall in 1963. Photo courtesy of John Graham.[/caption] Face, a member of the first and only expedition to ascend that particular route. That’s about as much detail as I retained. I’d heard the story from John before, but somehow it lacked meaning to me, a myth from another time, another place. Even when I’d asked to borrow gear, and John had beamed, announcing that this might be the start of a mountaineering life for me, my focus was on the free stuff.

I told Steve that Thursday, June 13, our planned summit day, was John Graham’s 77th birthday. I said I wanted to pay homage to a man with hips and quads no longer capable of taking stairs quickly, much less climbing stratovolcanoes. All of this was true, but I mostly wanted to avoid renting expensive gear at the last minute.

Steve rubbed a thumb over the belt. “The stitching looks good,” he said. “Let’s do it.”

On June 18, 1963, John Graham (along with the harness I’d borrowed), and six Harvard Mountaineering Club buddies, parked a VW Microbus on the north side of what was then called Mt. McKinley. John wrote about this in Harvard Magazine for the 50th anniversary of the climb. The oldest among them was 23, and only one member of the group had big-mountain experience. They’d cut their teeth on New England’s rock cliffs and ice gullies, but they were about to take on the Wickersham Wall, a face of ice and rock rising more than 14,000 feet from the Peters Glacier to the north summit. Avalanches fell daily. The sun beat down on snow at the top, sending blocks of ice the size of shipping containers falling for thousands of feet. Winds kicked up by the impacts could flatten a tent a half-mile away.

John Graham and friends en route to Denali National Park in 1963. Historic photos courtesy of John Graham. Photo courtesy of John Graham.

John Graham and friends en route to Denali National Park in 1963. Historic photos courtesy of John Graham. Photo courtesy of John Graham.The expedition took 36 days. The team carried 70-pound packs across the Alaska tundra. Then, each member made five trips 1,200 feet up steep rock and ice to haul food and gear to the bottom of a protective buttress veining the mountain. From here, the group could ascend Denali with less avalanche risk.

Still, the dangers were everywhere. They battled blizzards and 55-mile-per-hour winds that forced them to crawl on hands and knees along one section near the summit. They relied on gear purchased from an Army surplus store and stuff they made themselves, including tents hand-made by one of the climbers. They fashioned snowshoes from aluminum tubing and nylon cords. They installed their own 350-foot pulley system to get food to the top of a cliff. They climbed at night, when the footing was better, the snow firmer. At one point, a falling rock the size of an anvil skimmed past John’s head (helmets weren’t yet standard mountaineering equipment – he’d acquire the helmet I borrowed for Rainier in the years following his Denali excursion).

They’d learn later that a bush pilot had reported them missing after seeing their footprints track into avalanche debris. When a snowstorm hid their tents from view for half a week, an AP wire carried the news of “Harvard Climbers Missing.” Worry spread across the country.

Through all of this, they made the summit. In Eiger Dreams, Jon Krakauer describes the Harvard Route, as it came to be known, as “so bold or foolish…that it still hasn’t been repeated.” At least one brave soul has perished in an attempt.

To John Graham, who spent a career in the U.S. Foreign Service, his climb up the Wickersham Wall remains one of his greatest achievements, a catalyst for a lifetime of adventures – first dodging bullets in wars and revolutions, and then, after a transformative moment in Vietnam, turning his life to building peace.

To this day, John half-jokes that if he’s terminally ill, he plans to start hiking up a volcano in a T-shirt and fall into a crevasse so deep nobody would ever find him. Currently, I’m the family member best equipped to help him do it. This is an unlikely scenario, of course, but I thought of it once I was actually on Rainier. Even if I never brought John to his rightful resting place, I could at least take his gear, perhaps one last time, into an environment where it felt at home. I had a responsibility to make the summit. There were other reasons for wanting to reach it – to prove my fitness, to be able to look at Rainier from back home in Seattle and say I stood atop it – but once I was physically scaling the mountain, I wanted to do it for John.

My crampon fell off for a third time beneath the Icebox, one of Mt. Rainier’s most dangerous locations. On Father’s Day, 1981, a large serac broke apart here, sweeping 11 people to their deaths. It remains the worst mountaineering accident in North American history. Their bodies are still interred in the glacier. Because of hazards, climbers must work to spend as little time here as possible.

“We need to get that fixed now!” Steve was appropriately stern. And probably frustrated. He’d used a utility tool to tighten my footgear on the previous break, only to have the issue recur. My lifelong friend Kyle, making this climb with me, stomped up from the back of the rope team and helped me clip in. Per Steve’s instruction, I used my ice axe to bang the metal toe bar against my plastic boot.

Disappointment Cleaver loomed in the darkness ahead. The cleaver is a 1,200-foot maze of rock, ice and snow for which this particular route up is named. The terrain makes it the most technical section of the climb, and the “trail” contains a hand rope anchored into snow and rock to help prevent climbers – should they fall – from sliding almost straight down.

I was nervous about the cleaver, but I was even more nervous about my crampon. I worried that it wouldn’t stay on while traversing uneven rocks for such a long, pitched stretch. And I feared that if it came off one more time, Steve would tell me I had to turn around, that this old gear was putting others at risk. I didn’t want any of that. So, ascending the cleaver, I walked as carefully as I could, making sure my feet were a good width apart, not clanging against each other. In a way, concern over my crampon made me a better climber. More deliberate, more sure-footed. John Graham would have approved.

At 12,300 feet, atop Disappointment Cleaver, several members of our larger 17-person group were turning around. One man begged to stay on, but his rope team was significantly behind schedule, and the guides told him he’d done well, but he was in no condition to keep climbing Mount Rainier. Others went back on their own volition, either fatigued or sick from the thin air, or both. With so many members of our group going down, the guides told us that anyone continuing on from here would have to summit – no more guides would be turning around.

I looked away from Steve, expecting he’d tell me it would be best for everyone if I headed to camp, rather than risk a crampon coming loose on the treacherous, snowy grade of the high mountain, which is pocketed with deep crevasses. But no such mandate came. I would summit Mt. Rainier, orange helmet, Midcentury Modern harness, screw-adjustable crampons and all.

I could practically see my helmet, harness and crampons transforming from laughingstocks into artifacts. And with that, I was starting to grasp the true significance of the Harvard climb.

The sun came out at about 13,000 feet, as the remaining climbers in our group zigzagged up the snow. I was tired and my head hurt, but mostly I felt a sense of euphoria. This is what John Graham loved. To be so high above the world that nearby mountain peaks look almost flat. To feel as close as someone can to leaving the planet without actually doing so. This is why he summited Denali five decades ago and spent a good chunk of his life making his way up mountains around the world. I wasn’t sure I’d follow suit, but at least I could understand its appeal. I told Kyle it was amazing how thrilling such a slow-moving activity could be – an adrenaline sport at a glacial pace.

The author’s RMI Expeditions-led climbing team on the summit of Mt. Rainier. Photo by Kyle Overkoetter.[/caption]

The author’s RMI Expeditions-led climbing team on the summit of Mt. Rainier. Photo by Kyle Overkoetter.[/caption] Back in Ashford, our group celebrated over pints. “We got grandpa’s equipment up there,” Steve said.

People around the picnic table chuckled. Another guide asked what the deal was with the old gear, and I shared the limited version – that John Graham was part of the first and only group to summit the north face of Denali. I hadn’t yet re-immersed myself in the full story.

“Wait, did he go to Harvard?” Steve asked.

I nodded.

Steve nearly spit out his IPA. He had recently returned from a successful trip up Denali, spending nearly a month staked out at a base camp higher than Mt. Rainier’s summit, waiting for the weather to turn so they could finally make the charge to 20,310 feet, the highest place in North America. Steve had read how the Harvard Route still holds up as one of the most epic feats ever accomplished in mountaineering, especially because it had been done with such rudimentary equipment. I could practically see my helmet, harness and crampons transforming from laughingstocks into artifacts. And with that, I was starting to grasp the true significance of the Harvard climb.

I have a tendency to not fully appreciate what older generations have done. Their accomplishments are often decades behind, and what we’re left with are the wisdoms. These takeaways and lessons learned are valuable – essential – to be sure. But in the present, they can cover up the past. Even though I know John continues to live a meaningful, active life – one that includes teaching democracy in Egypt and motivating anti-government activists in Zimbabwe – it can be hard to reconcile the man who once climbed the Wickersham Wall with the man who now has spent the last 20-something years living a mile into the woods on an island in Western Washington.

My trip up Rainier, wearing John’s equipment, gave me some insight into the truly impossible nature of the Harvard Route, and, by extension, John’s life. No longer were his stories just words or vague concepts that didn’t come into focus.

But my trip up Rainier, wearing John’s equipment, gave me some insight into the truly impossible nature of the Harvard Route, and, by extension, John’s life. No longer were his stories just words or vague concepts that didn’t come into focus. I knew what it felt like to have the wind whip across my entire body on an open face of snow. I knew what that harness felt like around my hips, the pull of the rope if I lost step with the climber in front of me. I knew the glory of standing in a place where there was truly no more “up” remaining. John Graham is still the man who climbed one of the biggest and most dangerous mountain faces in the world and lived to tell about it. And that accomplishment was just the beginning. I’m starting to appreciate, in earnest, that John is, and always has been, a badass.

Two days after standing at 14,410 feet atop the Columbia Crest, overlooking the summit crater and the rest of the world, I visited John. On his front lawn, I regaled him with the saga of the climb. I told him about the ways his crampons tested me, but how, in the end, they stayed on. When I got to the part about the adjustment requiring a screwdriver, he nodded. “How else would you tighten a crampon?”

After I finished, John hugged me and told me he was proud of me. I started to say that his gear was primed, he could get back out there, summit Rainier himself again. After all, John Muir was climbing into his 70s. But John Graham stopped me. His days way up in the mountains are gone, and even if I’ve started to understand what it took to climb the Wickersham Wall, I’ll never comprehend how difficult it is for someone like John to know that he won’t ever again stand atop a

high peak.

He asked when I was planning to next climb Rainier. At that point, my legs still ached and one of my big toenails was black and blue from the constant slamming going downhill. Nearby, my 18-month-old daughter scaled the porch steps. She’s a climber, up and down everything in sight, always working her way to the tallest parts of playgrounds.

I told John I wasn’t sure when my second ascent would be. But I was already thinking that my daughter will be eligible to summit with RMI in 14 and a half years, and it’d be nice to experience it together. I don’t think John Graham will mind one bit if we opt for modern crampons.

Andrew Waite has an MFA in creative writing from Pacific University and a bachelor’s in journalism from Boston University. He works as a writer and editor in Seattle, where he lives with his wife and daughter. aawaite.com