Before we see our destination, we smell it. We’re walking a new logging road through an ancient forest; the trees are beginning to get smaller with elevation. The road follows Smitheram Creek, a tributary to the Skagit River, into an alpine bowl in the Canadian North Cascades. The citrusy smell of living, growing fir and spruce needles perfumes the air around us. Then, air blows down the narrow creek valley, pushing out the forest aroma and carrying a different smell: sawdust.

Half a mile later, we round a bend and see the smell’s source. At nearly 5,000 feet of elevation in the North Cascades, next to a green meadow in an avalanche path, we see the clearcut. It’s one of four cutblocks totaling 168 acres that was auctioned off by B.C. Timber Sales – the government organization that manages logging on Crown Land – and cut in summer 2018.

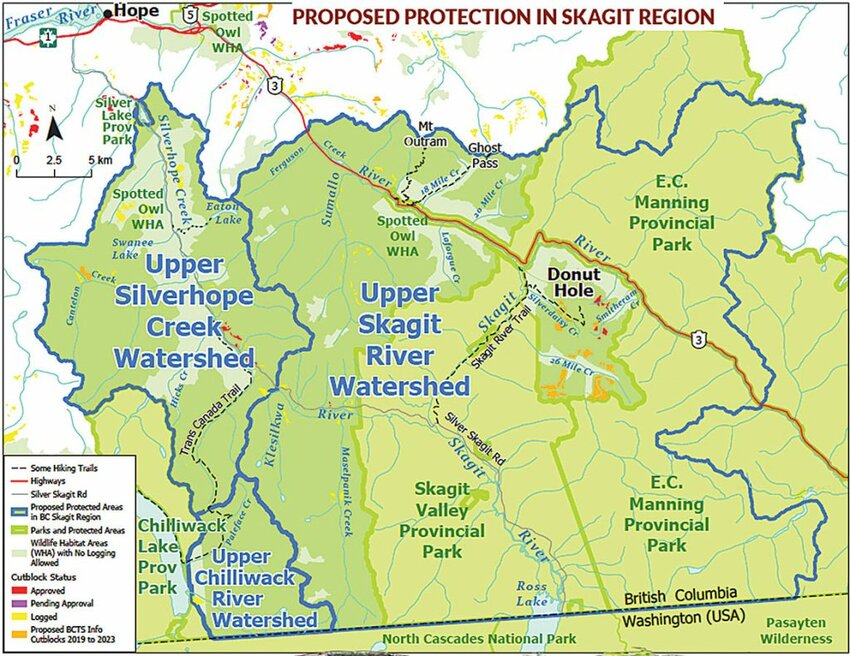

All four clearcuts are in an area known as “the Donut Hole,” a Manhattan-sized chunk of unprotected land sandwiched between E.C. Manning Provincial Park and Skagit Valley Provincial Park, 15 miles from the U.S. border. Both parks connect to North Cascades National Park, and together with the surrounding wilderness areas, national recreation areas and national forest, make up an immense chunk of wild lands that span the border.

Map courtesy of the Wilderness Committee.

Map courtesy of the Wilderness Committee.The Skagit River drains most of that area, starting in the clearcuts we came to see – as well as countless other peaks, tarns and wetlands – and flowing into Ross Lake, Diablo Lake, out the long Skagit Valley and into the Salish Sea. The Skagit is the only river in Washington state with all five northern species of Pacific salmon and the state has invested millions into the river for salmon recovery. It also hosts endangered bull trout and one of the largest wintering bald eagle populations in the lower 48 states.

“The Skagit puts more Chinook salmon in Puget Sound than any other system, more chum salmon than any other system in the lower 48,” said Joe Foy, co-executive director of the Wilderness Committee, a B.C.-based nonprofit, and my guide to the Donut Hole. “It’s just a beautiful river and a really valuable river.”

Joe Foy of the Wilderness Committee.

Joe Foy of the Wilderness Committee.Foy, who’s been working to protect the Donut Hole for decades, can’t help but swear about it: “Look at that shit.”

His knowledge of the situation makes it more offensive. Not only is it a scar in a wilderness that spans an international border, but it’s also a chunk of land that could be important for bringing grizzly bears back to the North Cascades – B.C. designated it a high priority for grizzly recovery. Additionally, Foy and many others feel that the clearcuts violate the spirit, if not the intent, of an international treaty governing the upper Skagit and other cross-border waterways.

That’s all trumped by what could come next.

The Donut Hole was left out of Manning Park, B.C.’s most visited provincial park, because of pre-existing mineral rights. Logging in the area is legal, but the clearcuts in a relatively pristine wilderness led to strong expressions of disapproval from both sides of the border last summer – Seattle mayor Jenny Durkan wrote a letter to B.C. Premier John Horgan, expressing “grave concern.” In response, B.C. put future logging in the Donut Hole on hold.

Then, in December 2018, a mining company with an environmental disaster on its resume applied for a permit for exploratory gold mining in the area. News of that permit application by Imperial Metals led to another international outcry – this time every senator from Washington, Idaho, Montana and Alaska signed a letter to Horgan, highlighting the risks posed by mining near headwaters of international rivers.

“While we appreciate Canada’s engagement to date, we remain concerned about the lack of oversight of Canadian mining projects near multiple transboundary rivers that originate in B.C. and flow into our four U.S. states,” the letter reads.

Dozens of elected officials, environmental organizations and tribal organizations on both sides of the border also voiced opposition to this permit, including Washington Governor Jay Inslee. Jon Snyder, Inslee’s senior policy advisor on outdoor recreation and economic development, said, “I think the important thing to remember in all these resource issues is that when we’re talking about extraction and mining, it’s often presented as an economic development issue: we want to mine here because it’s going to create jobs. Well it can also threaten jobs, in this case fishing, recreation, tourism. We’ve got to look at the whole picture.”

The Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs wrote to the president of Imperial Metals about the project, saying, “It is unacceptable for Imperial Metals to carry out any operations or actions that are not premised on full engagement or consultation with concerned First Nations parties.” The B.C. government’s own mining application text encourages applicants to “engage First Nations early and often as part of any planned development.”

Imperial Metals didn’t respond to an interview request before press time. In mid-August, eight months after receiving the permit application, the B.C. government still had not made a decision.

The upper Skagit River near Cayuse Flats, just downstream of the Donut Hole.

The upper Skagit River near Cayuse Flats, just downstream of the Donut Hole.Mt. Polley Mine disaster

According to the Imperial Metals application, the exploratory mining would involve building roads, helicopter landing sites, air strips, boat ramps and settling ponds to be used for five years. The company would drill to depths of 2,000 meters from two “mother holes,” and then drill directionally off of those deep holes.

Mineral samples from the area show a low gold ore density, according to a B.C. government report on the mining claim. Activists speculate that mining the claim wouldn’t make economic sense for Imperial Metals and that it’s a play to sell its mining rights for more money.

“I do not think this is economic, I think all they’re trying to do is push up the acquisition price,” said Ken Farquharson, a former commissioner of the Skagit Environmental Endowment Commission and founding member of Sierra Club B.C. He’s been working to defend the upper Skagit Valley from development since the 1960s.

On August 4, 2014, a tailings pond full of toxic copper and gold mine waste at Imperial Metals’ Mt. Polley mine, about 150 miles south of Prince George, B.C., breached, spilling an estimated 6.6 billion gallons of waste into Polley Lake, Quesnel Lake and other nearby waterways. Local officials declared a state of emergency. Fish sampled in the lake had levels of selenium above safe levels for human consumption. Testing near the spill found elevated levels of copper, iron, manganese, arsenic and other metals.

Tailings ponds are an acidic soup of rock particles and chemicals used for mineral extraction that often react together, creating dissolved metals. Dissolved copper (one of many minerals present at Imperial Metals’ claim in the Donut Hole) is toxic to many freshwater species. It can damage salmon’s sense of smell, which they use to find their upstream to their spawning grounds.

The Mt. Polley spill hurt tourism and other industries in the area, though people are once again swimming and fishing in Quesnel Lake. It remains one of the worst mining disasters in Canadian history and experts say it could take decades to learn the full extent of the damage. Five years later, Imperial Metals still hasn’t been charged for the disaster.

High Ross Treaty

The Oregon Treaty of 1846 set the border between the U.S. and Canada at the 49th parallel. The ruler-straight line doesn’t regard watersheds or ridgelines, causing a number of cross-border resource issues. For the Skagit River, the issue of logging and mining is only the latest in nearly a decade of conflict and resolution surrounding the river’s headwaters.

In 1942, Seattle City Light, hungry for more electricity for Seattle, began negotiating an agreement with B.C. to raise Ross Dam, which would have flooded 5,000 additional acres of B.C.’s upper Skagit Valley. The B.C. government made the agreement public in 1967, to much protest, and then began renegotiating.

The talks led to an agreement: Seattle City Light wouldn’t raise the dam, and B.C. would sell the utility company power for the rate it would have gotten from a bigger dam. The two nations made that agreement formal in the 1984 High Ross Treaty. That treaty also established the Skagit Environmental Endowment Commission (SEEC) to manage an endowment fund to preserve the upper Skagit watershed.

Among its many goals, SEEC was charged with working to acquire logging and mineral rights in the Donut Hole. Since it’s an international treaty, one might expect that the B.C. government would be helpful in securing SEEC’s goal of acquiring mining rights. That hasn’t been the case: B.C. Timber Sales didn’t even inform SEEC about last summer’s logging in the Donut Hole.

“Acquiring it is part of our mandate. I believe that we will continue to work to try to facilitate the purchase of it. As for how we’re doing it, we’re just moving forward on our intent,” said Tom Curley, SEEC co-chair.

Why log the Donut Hole?

Foy and I continue walking, the surrounding scenery still beautiful despite the logging scars. We reach the first clearcut, where there’s no trace of life, not even fireweed growing in the fresh cut. Many of the stumps are the diameter of a human arm.

Looking at the road carved into the mountain and the size of many of the stumps on the clearcut, the finances don’t add up to Foy. B.C. Timber sales funds road construction, then auctions licenses to harvest timber. “I find it very hard to believe that in any free market this made any economic sense,” he said. “I get that some guys were paid to cut trees and drive logging trucks, but the whole show? I don’t believe it. And apparently I don’t have the right to see the whole accounting.

“So again I say, what the hell are you guys doing up here? You’re in the middle of parks and supposedly your top priority for getting grizzly bears back. You’ve got an international treaty. What are you doing? Because it doesn’t look like you’re making money for the people.”

In response to a question about how much it cost to build and improve roads into the Donut Hole, a spokesperson for B.C.’s Ministry of Forest Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development said in an email, “the cost of the road was paid for by BCTS, which is a self-financing organization.”

While nearly all remaining old-growth in the U.S. is off-limits for timber harvest, that’s not the case in Canada. About 90 percent of Canada is public land, and nearly all of that is open for logging, mining or other resource extraction.

According to a 2017 report by the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, 10.6 percent of the Canadian landscape is protected for nature. That lags behind the global average of 15 percent and puts Canada last among G7 countries in protecting wilderness. In some ways, Canada hasn’t dealt with the issue of how to have a successful timber industry while also setting aside old-growth for habitat and recreation.

For the government, it’s a difficult time to halt logging in B.C. After an outbreak of mountain pine beetles killed about half the marketable pine trees in the province, the B.C. Ministry of Forests increased the allowable annual cut in the early 2010s – doubling it in some areas – to allow the industry to harvest the timber while it still had value.

The bonanza is ending, mills are closing and timber industry workers are unemployed. The industry has a “pine beetle hangover” and the government doesn't want to be seen as harming timber jobs, Foy said.

What’s next?

The B.C. government has been quiet about the Donut Hole this summer. It accepted public comments on Imperial Metals’ mining application until May 17, and it is still consulting with First Nations.

“The permit application is currently with the statutory decision maker, who will make a decision when they have completed a thorough review of all input submitted,” a spokesperson for the Ministry of Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources said in an email. “The ministry makes a serious effort to consider and weigh all relevant information and perspectives, and is committed to conducting a thorough and comprehensive review.”

Foy and I wander farther, to the end of a new logging road. We’re the only people in this bowl. It is the headwaters of a celebrated river, but for the moment this chunk of land feels forgotten.