Those in the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community are known as the Salmon People. They are descended from the Swinomish, Kikiallus, Samish and Lower Skagit tribes, who inhabited Skagit Valley and the Salish Sea islands for thousands of years before European colonization.

With their ancestral lands at the mouth of the Skagit River, these Coastal Salish tribes centered their culture on abundant saltwater resources like salmon and shellfish and upland resources like cedar, berries and wild game. Still today, members of the tribal community rely on salmon fishing and shellfish harvesting at the river’s end.

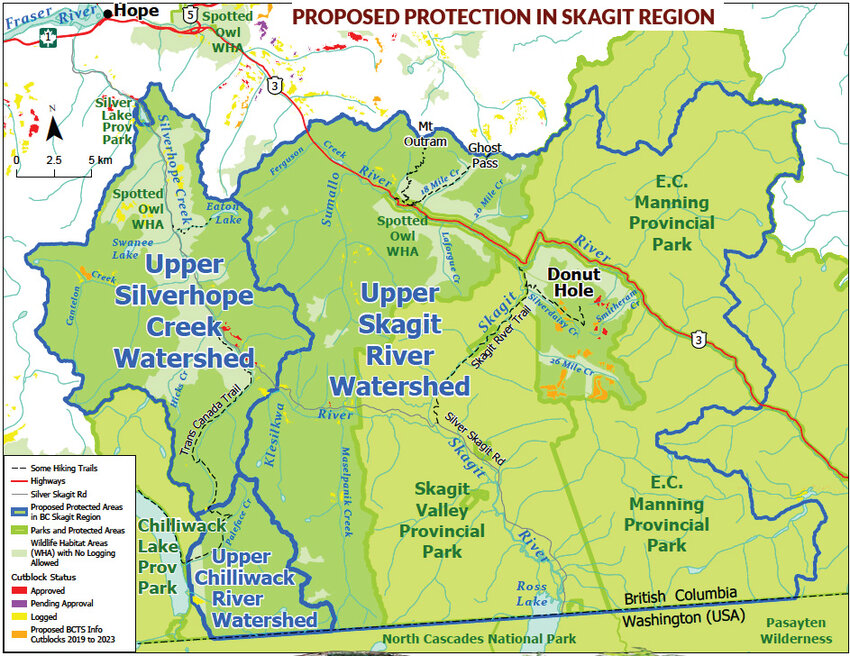

The 150-mile-long Skagit River drains from an area known as “the Donut Hole,” a Manhattan-sized chunk of unprotected land in B.C. sandwiched between E.C. Manning Provincial Park and Skagit Valley Provincial Park, 15 miles from the U.S. border. Both parks connect to North Cascades National Park, and together with the surrounding wilderness areas, national recreation areas and national forest, make up an immense chunk of wild lands that span the border.

The area, which was subject to 168 acres of clear-cutting by B.C. Timbers Sales in 2018 and has since been prohibited after an outpouring of concern from both sides of the border, remains at risk of exploratory mining.

In December 2018, Imperial Metals applied for a permit for exploratory gold mining in the area. News of the application raised concerns from U.S. and Canadian government officials, tribal communities and first nations expressed in letters to B.C. premier John Horgan in the summer of 2019.

The B.C. government has yet to make a decision on whether it will allow exploratory mining in the area; meanwhile, the opposition continues to grow.

Washington Wild, a nonprofit organization that protects wild lands and rivers in Washington, has coordinated an international coalition of U.S. and Canadian stakeholders to resist the proposed mining. A total of 280 local and state governments, tribes, businesses and other communities downriver and in B.C. have signed on against the pending mining contract. The list includes governor Jay Inslee, Seattle mayor Jenny Durkan, U.S. senators Patty Murray and Maria Cantwell, Lummi Nation, Patagonia and many others.

Washington Wild, a nonprofit organization that protects wild lands and rivers in Washington, has coordinated an international coalition of U.S. and Canadian stakeholders to resist the proposed mining. A total of 280 local and state governments, tribes, businesses and other communities downriver and in B.C. have signed on against the pending mining contract. The list includes governor Jay Inslee, Seattle mayor Jenny Durkan, U.S. senators Patty Murray and Maria Cantwell, Lummi Nation, Patagonia and many others.

Amy Trainer, environmental policy director for The Swinomish Indian Tribal Community, said the Swinomish were one of the first communities to write to Horgan in 2019, and have since joined the coalition. “This is wrong. It is antithetical to salmon recovery and protection numbers, to the health of the Skagit River ecosystem,” Trainer said of the proposed mining.

The Skagit, which flows into Ross Lake, Diablo Lake, out the long Skagit Valley and into the Salish Sea, is the only river in Washington state with all five northern species of Pacific salmon. The state has invested millions into the river for salmon recovery. It also hosts endangered bull trout and one of the largest wintering bald eagle populations in the lower 48 states.

“The Skagit puts more Chinook salmon in Puget Sound than any other system, more chum salmon than any other system in the lower 48,” said Joe Foy, co-executive director of the Wilderness Committee, a B.C.-based nonprofit. “It’s just a beautiful river and a really valuable river.”

Nearly three years later, it’s still under threat.

Imperial Metals

Imperial Metals mining operation would involve building roads, helicopter landing sites, airstrips, boat ramps and settling ponds to be used for five years, according to the application. The company would drill to depths of 2,000 meters from two “mother holes,” and then drill directionally off of those deep holes.

Some those who have joined the coalition say that Imperial Metals is a bad actor.

On August 4, 2014, a tailings pond full of toxic copper and gold mine waste at Imperial Metals’ Mt. Polley mine, about 150 miles south of Prince George, B.C., breached, spilling an estimated 6.6 billion gallons of waste into Polley Lake, Quesnel Lake and other nearby waterways. Local officials declared a state of emergency. Fish sampled in the lake had levels of selenium above safe levels for human consumption. Testing near the spill found elevated levels of copper, iron, manganese, arsenic and other metals.

Tailings ponds are an acidic soup of rock particles and chemicals used for mineral extraction that often react together, creating dissolved metals. Dissolved copper (one of many minerals present at Imperial Metals’ claim in the Donut Hole) is toxic to many freshwater species. It can damage salmon’s sense of smell, which they use to find their way upstream to their spawning grounds.

Tailings ponds are an acidic soup of rock particles and chemicals used for mineral extraction that often react together, creating dissolved metals. Dissolved copper (one of many minerals present at Imperial Metals’ claim in the Donut Hole) is toxic to many freshwater species. It can damage salmon’s sense of smell, which they use to find their way upstream to their spawning grounds.

The Mt. Polley spill hurt tourism and other industries in the area, though people are once again swimming and fishing in Quesnel Lake. It remains one of the worst mining disasters in Canadian history and experts say it could take decades to learn the full extent of the damage. Imperial Metals still hasn’t been charged for the disaster and, according to its website, continues to drill near the area.

Hope

U.S. and Canadian governments made a pledge to protect the Skagit River watershed. In agreement to raise Ross Dam, Seattle City Light and B.C. governments formed the 1984 High Ross Treaty, which also established the Skagit Environmental Endowment Commission (SEEC) to manage an endowment fund to preserve the river’s watershed. SEEC has made the purchasing of the Donut Hole’s mineral rights one of its goals.

Also, other than the pending application, there’s little evidence to suggest Imperial Metals will be drilling in the Donut Hole anytime soon.

Foy, who has been working to protect the Donut Hole for decades, said Imperial Metal has no intention to build a mine at the site.

Imperial Metals applied for mining rights when word spread that there may be gold in the area, but, according to Foy, there’s no gold. The Donut Hole has been mined for over 100 years and no gold has been found, he said.

Mineral samples from the area show a low gold ore density, according to a B.C. government report on the mining claim.

What they’re doing is “jacking-up the price,” he said. They are sitting on a claim, waiting for the government to buy them out. “Which they should do,” he hopes.

Foy believes the B.C. government should buy back the mining claim from Imperial Metals, return the land to environmental groups and First Nations and help restore the area. There are mining tunnels from the 1920s that need to be assessed to see if they are polluting Skagit waters, he said.

"After a century of blasting, drilling and tunneling to find a workable mine with no luck whatsoever, it's time for British Columbia to extinguish Imperial Metals' mineral tenure in the Skagit Headwaters Donut Hole and then, with First Nations, protect the place,” Foy said. “B.C. must also enforce an Imperial Metals cleanup of the site, which is strewn with a hundred years’ worth of garbage, waste rock and mine drainage left behind by years of fruitless exploration."

He also said although the area may not be at risk of further mining, the continued support from communities on both sides of the border is necessary and appreciated.

Tom Uniack, executive director for Washington Wild, said opposition to proposed mining in the Skagit headwaters continues to grow as downstream governments begin to learn about the mining threat. “The potential impacts to downstream values such as safe and clean drinking water, irrigation for local farms and agricultural businesses and recovery efforts for federally endangered salmon and orca whales are both unacceptable and unnecessary,” he said.

The momentum and support of all these communities is overwhelming, Trainer said. “And it just continues to grow.”

Trainer said if the B.C. government denies the application, it could be a win-win situation for B.C. First Nations, Washington tribal nations and environmental groups on both sides of the border.

This story is an update to previous Mount Baker Experience reporting by Oliver Lazenby. That story can be found here. x