Photo by Travis Moose.

Photo by Travis Moose.If you’ve ever taken the Whatcom Chief out to Lummi Island, you’ve probably seen reef net fishing gear on the water or being hauled up across from Legoe Bay. With only 12 such gears in the world – and all of them located here – it’s hard to imagine that at one time there were dozens of similar setups that allowed fishermen to haul in migrating salmon without running the risk of incidental bycatch, overfishing, or polluting the local environment.

Photo by Travis Moose.

Photo by Travis Moose.More than two centuries ago, inside the same bay, members of the Lummi tribe hauled their canoes into the saltwater surrounding their ancestral land. During the summer months, salmon by the thousands rushed through the bays and inlets of the Salish Sea enroute to the Fraser River to fulfill their life’s goal of returning to their home river to spawn.

The Lummi made note of the salmons’ migratory patterns, observing the life cycles of different species: when each one arrived, what their habits were, how many could be counted. And they honored the fish – an animal revered for its life-giving force. For the Coast Salish people, the annual salmon return, and its celebration assured the renewal and continuation of life.

Intricately linked to that sense of reverence for the salmon was the way in which the Lummi fished for them.

“Two canoes with a scooped-shaped net between them were positioned parallel to each other in the path of the salmon running on the incoming tide,” note the authors of Shared Heritage: A History of Lummi Island. “The fish were guided to the net by long, false reefs that extended in a V-shaped formation from the canoes to buoys anchored to long rocks. When salmon were spotted from the canoes, the net was swiftly raised to trap the fish.” This method of fishing eventually became known as “reefnetting.”

In the early 1900s, the Lummi were forced to give up their traditional method of reefnetting when large fish traps, built by non-natives, were placed directly in front of their centuries-old fishing sites. However, in 1935 those environmentally destructive traps were outlawed—which opened the door for the return of reef net fishing. But the difference was that this time, non-Lummi fishermen were the ones waiting for the salmon to return.

Courtesy Washington State Archives.

Courtesy Washington State Archives.In place of cedar-bark, nettle fibers, stones, and beach grass, the reefnetters of the 20th century employed more modern materials and techniques. Collectively called a “gear,” this new equipment saw the evolution of canoe boats into more stable barges, artificial reefs constructed from high-performance plastic, and the introduction of solar-powered panels, sonar equipment, underwater cameras, and mechanical winches.

But what didn’t change was the way in which the salmon were caught.

Riley Starks has been fishing for 50 years and owns one of the dozen licenses available for reef netting. Originally working as a crab and gillnet fisherman in Alaska’s Bristol Bay, he was introduced to reef net fishing on Lummi in the early 1990s and realized that the island was destined to become his home.

“Reef netting truly defined the culture of the island,” he says. “Everybody either was a reefnetter or knew someone who was. Back in Bristol Bay, so many of the fishermen were only excited to talk about the money they’d made; but here, it was different.”

Photo by Travis Moose.

Photo by Travis Moose.Because in reef netting the fish come to you (versus actively pursuing them or setting out a purse seine to drag them in), the practice is more intuitive – allowing the captain and his crew to form a special kind of bond.

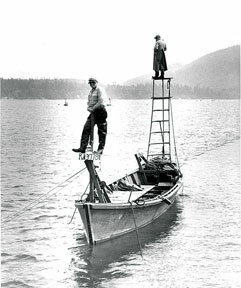

“When you’re out on the water, waiting for the guide fish to lead the salmon into the net, you’re either on the platform or up in the tower,” explains Starks. “Everyone is waiting for the same thing, so it feels very tribal. It’s quiet out there; there’s no noise from any motors. In those moments, it truly is the Zen of fishing.”

Nevertheless, everyone onboard the gear remains alert so as not to miss the opportunity they’ve been waiting for—and once that happens, all hell breaks loose. The spotter calls out from the tower to the crew below that the fish are heading into the net; then they’re immediately hauled up into live wells on deck. Once the fish are in those holding pens, they’re hand-sorted, and the accidental bycatch is safely returned to the water.

“Every other type of gear causes injury to the fish,” Starks says. “But not reef netting.”

Because reef net-caught salmon can be live-bled as they swim around the pens there’s no accumulation of lactic acid. The result is a high-quality product that is 100 percent sustainable, and that’s where Ian Kirouac comes in.

As president of Lummi Island Wild Co-op (LIW), Kirouac is responsible for getting the reef net-caught fish to market.

“Through Lummi Island Wild, we’ve built relationships with customers who seek out this type of quality. We don’t use polluting diesel engines, we return non-targeted species back into the water unharmed, and we are the only solar-powered commercial fishery in the world.”

Photo by Travis Moose.

Photo by Travis Moose.Kirouac came to reef netting via a circuitous route that led him from a planned career in marketing to owning two gears in Legoe Bay. Out on a schooner in 2003, the ship was passing by Lummi Island and the younger Kirouac saw the reef netters out on the water. He got himself invited onto one of the gears and “fell in love with it.”

“This is seafood you can be passionate about,” he says. “We are at the apex of quality and sustainability. The genetic fat content of the Fraser River fish is truly spectacular. In preparation for their metamorphic transition from salt-to-fresh water they burn up a lot of fat; with every kick of their fins, they lose some, so we’re catching Fraser River-bound fish at their prime.”

To prove his point, LIW tested some of the sockeye they’d caught, and it yielded almost a 15 percent fat content versus 9 percent of those in Bristol Bay. “This salmon is about as close to medicine as you can get,” he says. In fact, Kirouac—an avid hiker who’s now training for his first Ironman competition at age 49—is convinced that the LIW fish he’s eating will help power him to success on the course.

For Riley Starks, it lies in internship programs to teach the next generation of reef netters what it feels like to fish in harmony with nature, and to see Lummi tribal members return to the practice. But it’s also about working to save the Salish Sea itself. To that end, he founded the Salish Center for Sustainable Fishing Methods to educate people about the fragility of the sea, and how intricately linked the survival of the salmon is not only to reef netting, but to the southern resident orcas who also depend on them.

Courtesy Washington State Archives.

Courtesy Washington State Archives.Ian Kirouac’s vision is likewise focused on public involvement, but from a different perspective. “The only thing that’s going to ensure the survival of reef netting as a viable commercial fishery is market demand. People need to be willing to pay a bit more for quality, because without that, there is no chance for a future.

“Patagonia Provisions (a major buyer of reefnet-caught fish) says it best: Eating is activism,” he says. “There are reefnetters out there doing it right, but we need the public’s support to keep this practice alive.” X

Author’s note:

Lummi Island is the only place in the world where this fishing method is used and where passionate reefnetters live and work.

For more information about reefnetting and the products mentioned:

salishcenter.org

lummiislandwild.com

www.patagoniaprovisions.com/collections/salmon