Courtesy Jason D. Martin

Courtesy Jason D. MartinIt was 8:30 in the morning on January 4, 2003, and I was working in Red Rock Canyon near Las Vegas. We were approaching a climb when my client — we’ll call him Rob — pointed up at a cliff.

“Hey, there’s somebody up there. It looks like he’s about to rapp—”

He was going to say the word “rappel.” But that’s not what happened. The person was not a climber, and he wasn’t attached to a rope. Instead, he was a hiker that was in the process of losing his footing. He stumbled backward, stepped back over the edge…

…and fell.

The man cartwheeled silently through the air, falling 60-feet into a series of shallow interwoven canyons. The hollow thump of his body hitting the ground echoed through the empty park.

“Oh my God!” Rob and I both screamed, staring at one another wide-eyed.

I gave him my cell phone and told him where to go to get service, and then scrambled down into the shallow maze of rocks beneath the cliff. It took me a few moments to find the middle-aged man. He was upside down, jammed between the rocks. There was nothing I could do with my tiny first aid kit.

The man was dead.

By 10 that morning, we’d filled out police reports and were told we were free to leave.

“Do you still want to go climbing?” I asked.

Rob thought about it for a moment, and then said, “Yes.”

And so we climbed. We stationed ourselves on a wall I regularly taught at, slightly above where the man had fallen. We had about as good a day possible given the circumstances, one of which was the visible removal of the man’s remains in a body bag a few cliff bands below.

This was a terrible mistake.

Rob and I had just been through a deeply traumatic experience. We had watched a man die. But we tried to treat it as if it were a normal day of climbing. We tried to act as if nothing had happened.

At the time there wasn’t a strong understanding of traumatic stress injuries in outdoor recreation. People were certainly talking about post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), but they weren’t broadly looking at it through a civilian lens. Instead, it seemed to be something that was reserved for those coming back from war zones.

Something happened to me after that incident. I didn’t want to go climbing, even though I was making my living as a guide. My wife told me I was unusually quiet. I was tired. I was introverted. I had nightmares.

Every single part of what I experienced maps directly to what we now recognize as a traumatic stress injury. I did recover after a few months. But if I had recognized that what I had been through caused an injury, perhaps I could have recovered in a healthier manner. Perhaps I could have sought out treatment. Perhaps I could have offered Rob some psychological first aid as well…

Courtesy of Responder Alliance

Courtesy of Responder AllianceInterestingly, it has been documented that outdoor recreation stress injuries can occur even when there are no physical injuries. A rockfall incident nearby, a close call with an avalanche, a leader fall or even being lost in the woods for a short period can all lead to a stress injury.

When we see someone fall and get injured in an outdoor setting, we respond in a very specific way, a way for which many of us have been trained. We respond with first aid.

Wouldn’t it make sense to respond to a psychological trauma the same way? What if we in the field were able to recognize a stress injury and treat it just like a broken bone? And then when the person left the field, they could be elevated to a higher level of care? The person with the broken bone is brought to a hospital for treatment. The person with a stress injury is referred to a therapist or a peer counselor.

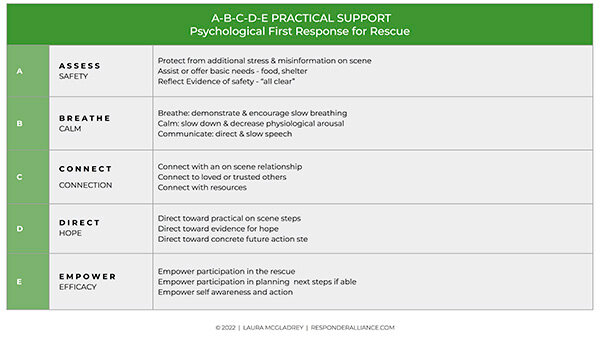

This type of thinking really began to make its way into the consciousness of outdoor recreationalists and professionals in the late 2010s. Nurse practitioner and wilderness medicine instructor Laura McGladrey popularized it. McGladrey has worked extensively with stress injuries amongst mountain rescue teams and ski patrol crews. She became a name in the outdoor industry by speaking at events like the Mountain Rescue Association annual meeting and on episode 34 of the Sharp End Podcast, a podcast that explores technical mountain accidents and how to avoid them.

McGladrey founded an organization called the Responder Alliance (responderalliance.com), which teaches people the art of psychological first aid. Indeed, since McGladrey’s work and her organization have come onto the scene, many wilderness first responder courses have begun to implement this as a part of their curriculum.

Created by Laura McGladrey. Courtesy of the Responder Alliance.

Created by Laura McGladrey. Courtesy of the Responder Alliance.Obviously, some injuries have more impact than others. There are few things worse than losing someone you know — a friend, a spouse, a child — in a mountain accident. And there’s nothing worse than being with the person when it happens.

Several years ago, the American Alpine Club recognized that many who’d experienced this kind of trauma didn’t have the means to manage their grief with a mental health professional. The result of that was the development of the Climbing Grief Fund. The fund’s mission is to connect “individuals to effective mental health professionals” and to evolve “the conversation around grief and trauma in the climbing, alpinism and ski mountaineering community.”

Many of us have lost a friend or a loved one in a mountain accident. Many more of us have experienced some type of stress injury around something that happened to us, to a partner or to someone else nearby. And some of us have been first responders to traumatic accidents. It is normal and human to have emotions around this type of thing.

Our entire community has work to do. We need to do a much better job of normalizing the treatment of stress injuries and grief around accidents that take place in the mountains. We need to understand how these injuries impact people, and help each other find support.

Jason D. Martin is the executive director at the American Alpine Institute, a mountain guide and a widely published outdoor writer. He lives in Bellingham with his wife and two kids.