The writer, Jason Hummel, looks on over the Columbia River. Chris Starling photo

The writer, Jason Hummel, looks on over the Columbia River. Chris Starling photoAcross the years and plains of those days unmarked by adventure, there are those ranges of memory that have become the mile markers to my life. Among them are those goals that set me on the road, a nitro boost to pull me away from that equal and opposite desire to watch the rain fall, the pages of a good book flip by and days spent in warmth and company.

It was one such goal, my desire to truck across the length of Washington state, north to south, that drove me forward. By small and great degrees, I progressed on this goal. Some trips were a day, others weeks, and in total this project took 93 days of effort and spanned 21 years.

Routes: North to South

Hannegan to American Border Peak, May 30 to June 1, 2022

Mineral High Route, June 5-8, 2003 and in 2010 and 2022

Picket Traverse, February 17-22, 2010 and in 2022

The Isolation Traverse, June 4-10, 2011 and in 2013

The Forbidden Tour, March 7-9, 2015

The Ptarmigan Traverse, June 29 to July 5, 2008 and in 2011 and 2013

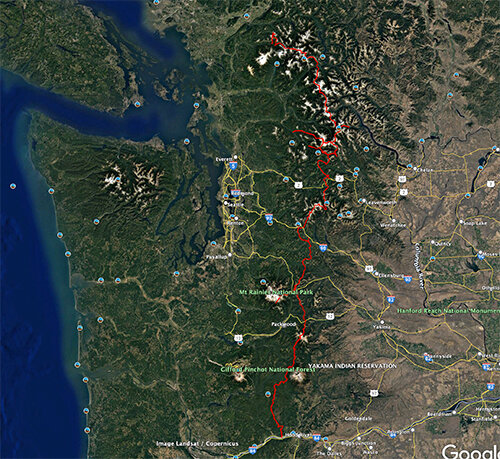

Map of Jason Hummel's route across Washington state. Courtesy Jason Hummel

Map of Jason Hummel's route across Washington state. Courtesy Jason HummelThe American Alps Traverse, June 2-17, 2013

Dakobed Traverse, June 30 to July 5, 2009

Sauk River to Highway 2, April 7-12, 2016

Stevens to Smithbrook Road, April 9, 2017

14 Lakes Traverse, March 29 to April 1, 2021

Alpine Lakes Traverse, July 3-8, 2010

The Patrol Race, February 8, 2014

Crystal Mountain to I-90, March 30 to April 2, 2017

Paradise to Crystal Mountain, February 4-6, 2012

Crystal Mountain to White Pass Ski Area, January 14-16, 2022

The Goat Rocks Traverse, July 3-5, 2001

Old Snowy from White Pass, February 8-9, 2003

The Columbia Traverse, February 18-25, 2022

The Missing Link

Never was a plan so simple: Go over a mountain, then another and so forth until the Canadian border was at hand.

Shifting my RV into park, I stepped from its entryway onto the shores of the Nooksack River. The waters grumbling like a mountain with a tummy ache, the rain casting about like sheep being rounded up, the forest shaking rain out like a wet dog. Atop a great boulder, I sat on the shore and listened. The melody was as Washington to my ears as any tune could be.

Forest McBrian crosses Luna Cirque during a Picket Traverse in mid-winter. Jason Hummel photo

Forest McBrian crosses Luna Cirque during a Picket Traverse in mid-winter. Jason Hummel photoGoing back 21 years, and hundreds of miles southward, a younger me climbed to the top of Mt. Curtiss Gilbert, so dedicated by the longest serving Supreme Court Justice, William O. Douglas; although misspelled on maps today with one “s” instead of two. Curtiss Rickey Gilbert (1894–1947) was a boyhood friend of Douglas’s. He was also a youth leader and mountain climber. Many years ago I ran into his family climbing Curtiss Gilbert, some half century since his passing.

Unlike Gilbert’s family, I was going beyond his namesake and traversing the Goat Rocks, unknowingly completing the first link in a grand traverse, one that I eventually conceived of stretching the full length of Washington state, from Oregon to Canada. In 2003, I’d add two more links, the Mineral High Route and White Pass to Goat Rocks. In years to come, the chain would grow with the addition of the Ptarmigan, Isolation, Forbidden, Pickets, 14 Lakes, Columbia Traverse, etc. Nineteen links in total, many overlapping one another.

I get asked, “So did you follow the Pacific Crest Trail?”

The short answer is rarely, but that doesn’t entirely quantify the difference. One is a trail and beautiful, but a trail all the same. The other is glaciers and peaks, passes and slopes where any one path can be evolved to weather and snowpack, whim and fancy. Unlike predetermined trails, ski routes in the high country benefit as much from poetry as technique and discipline. They are trails made, rather than trails followed.

The combined route I called the Washington Traverse. A simple name, given more as a placeholder, yet survives as I lack a better term for it.

Back at my RV in the North Cascades, I cracked my door for a weather report, parroting all local weathermen’s favorite forecasts by saying, “Today will be mostly cloudy with a chance of scattered showers.”

Over the next hour, I stashed my mountain bike on Twin Lakes Road and drove to Goat Mountain trailhead. Both ways I was white-knuckled. My home-on-wheels wasn’t built for such a wet, tree-strewn and potentially snowed-in road.

A half an hour later, shoulders heavy with gear, I set out alone. On every other leg of my journey, I’d had partners along. Given that another dreary week of weather was bookended by similarly weather-challenged weeks, which together stretched into months, I can’t fault the fact that no one wanted to join me on yet another wet adventure.

Kyle Miller ascends the Dorado Needle Couloir. Jason Hummel photo

Kyle Miller ascends the Dorado Needle Couloir. Jason Hummel photoWith a snow line a few miles distant, it was up to memory to entertain. Recollections that stretched southward through space and time, back to when ghosts of fog on Fortress Mountain broke apart only to have a Brocken spectre appear. Or when the northeast face of Mount Fury glowed in beams of starlight like an ancient spaceship preparing to take flight. Or when, farther south, thunderclouds spilled over the horizon atop Glacier Peak and the ambient power in the air sizzled and buzzed across our metal equipment and stood our hair on end. Or the quaint moments, such as when a rainbow framed the McAllister Glacier, or when my friend Kyle Miller argued with a marmot. Or when my brothers followed me through two days bushwhacking only to reach Bridge Creek, a short way from the road, to read a sign that declared that “The bridge is out, bushwhack at least one day to reach the road.” Or that time on Mt. Challenger during a long nap on Perfect Pass when I sunburned my feet so badly that they tore completely open, scabbing from toe to ankle, and since I’d lost my shoes on Mineral Mountain, I was forced to walk 20 miles of dry trail in my ski boots.

Memories compass spun in circles as I returned to my first ski traverse. In the late ’80s my father, Kurt Hummel, became the founding president of the Mt. Tahoma Trails Association (MTTA). It was during a series of adventures that he, in order to get government funding, needed to prove the feasibility of creating a ski trail. As such, he conceived a weeklong ski traverse from Golden Lakes to the end of West Side Road where it meets the Paradise Road.

There are many stories from that first ski traverse. Snow, forest and trees. Frozen lakes. Sharp blue skies that only winter shapes. The endless everything coated in white. The paths blazed. This all planted a seed.

And the seed bore fruit.

Back in the present, I reached continuous snow on Goat Mountain and comically, I sighted goat tracks and followed them to the summit. Scanning the horizon, I could see the end, the Canadian border. Just then, sunlight broke through thick and heavy clouds. Like a top hat, I swung this way and that way, snapping photos like a fish does flies.

Mike Traslin descends by seracs on the Forbidden Traverse. Jason Hummel photo

Mike Traslin descends by seracs on the Forbidden Traverse. Jason Hummel photoMy skis on, the slurry of snow before me swung out from every turn, slowly avalanching. At the base of Winchester Mountain, I went to shelter under a tree from the constant rain, but soon realized there was no escape. Hood pulled up, I contemplated my next move. Usually I climb a couloir to the top of Winchester Mountain, but soupy snow gave me pause. When I did summon the courage to leave, the rain pushed me back. “It’ll get better,” I grumbled, so I waited. Two more times I was repelled. Finally growling, “To hell with it” I set off, fingers crossed for improved weather the following day. Most certainly they’ve gotten it right just this once (because didn’t you know that weathermen are the unsung heroes, like accountants, lawyers, cops and insurance agents, at least when they are on your side).

Fresh bear tracks took me to the top of Winchester and the old fire lookout. Broken boards and torn out nails greeted me. I’d like to say it was the bear, but it looked like humans had torn the storm door apart, so they could gain entry. The actual door was open, and snow filled the entire structure. Such carelessness broke my heart.

Come morning, a bright smile from a long lost friend grew and shone. “Hello Sun. Kick your shoes off. Stay awhile.”

Since I was going on a day trip to the border and back, I broke camp and moved everything down the mountain to a lower pass, where I stashed it. Suddenly lighter and gravity in my favor, I pointed ski tips to the valley and, suddenly, found myself laughing. Why? Because the snow was so bad. I’ve skied bad snow. I know what bad is and, this, (in all directions) was so very bad. Even with every skill initiated, I only avoided disaster in my descent through the icy crust by curving my trajectory up the southern wall of a small vale.

Another rise and descent brought me to another good viewpoint. That day's snow wasn’t as unstable as I expected. Incoming haze and clouds, along with a breeze, helped. Better yet, I saw a low route I could take on my return that mitigated my risk of slides. Even though an earlier shedding brought much of the snow down two days earlier, there was hangfire on those slopes.

The compass pointed due north. Any magnetic disturbances ceased: Avalanches, snow conditions, route finding, etc. were all a go. Indecision was overwritten by forward motion.

Hours of slogging with a capital “S” were my reward. Every single step felt like I was towing the entirety of my grand traverse along for the ride.

A corniced ridgeline gave way to gentle slopes. No force field was in evidence. Just a loneliness as real on one side of the Canadian boundary as the other. A moment to me as big and bursting with excitement, but without the fireworks. I celebrated with a quiet smile, and sadness, as the way had been fulfilling and rich in memory, the greatest of treasures. Twenty one years is a long time, long enough for a child to become a man once more, and I’d changed much in these many years.

With regret, I slid back over the ridge. The wind picked up and the forest oooed and ahhhed. Washington’s spring quartet in concert just for me? Home is where the heart is, so they say.

Chris Starling skis through heavy snowfall on the Columbia Traverse. Jason Hummel photo

Chris Starling skis through heavy snowfall on the Columbia Traverse. Jason Hummel photoThe inevitable regress suddenly flew by. Snow felt light and fluffy, legs of jelly grew strong, and wind was at my back, pushing me forward. One climb after another, bowls and cirques, slopes and forests fell behind me until, at last, I’d come full circle.

Cold and clouds hung over me as I packed my overnight gear. From the col below Winchester’s summit, I cast my eyes northward. I took a moment, a sliver of time carved from reality. Much like a photograph, they are taken, except with emotion and soul included. I snapped one here and put it in my mental album. After, I turned my skis downslope.

The last big descent of my trip was a 2,000-foot couloir. Another laugh escaped me when I dirted-out at a waterfall midway through. Thrill dashed on the rocks like my skis, and I left as much P-tex behind on the lower half of the line as the upper half. No ski of mine is new and shiny for long.

At Twin Lakes Road miles passed on snow that at times felt like it was impersonating gravel. There was enough pollen to coat my skis in a thickened tar-like consistency that I’d hardly have needed skins to climb at all. Not so good for the way down, sadly.

After three or four miles on Twin Lakes Road I bashed through the woods to where my bike was hidden. With a ski-endowed pack, I raced down the road like a galloping elk. Wind in my face, speed faster than any skiing I’d had in days, and then there it was — that smile. That thrill engaged me. Most excellent the finish line is when you’ve the wings of success to carry you forward.

Jeff Rich laying down on Easy Ridge exhausted while crossing Picket Traverse. Jason Hummel photo

Jeff Rich laying down on Easy Ridge exhausted while crossing Picket Traverse. Jason Hummel photoWay too fast and far too reckless, I reached Highway 542. Drivers must’ve taken a few looks at me and wondered, “Why?” I’m a skier, and I would’ve asked myself as much. Taking a left after a quarter of a mile was a relief; I was back on gravel and out of eyesight. Only then, in my peripheral vision, a movement caught my eye. Suddenly a bear and I were mere feet apart, facing off. I stopped, cast my eyes downward, and slowly backed around the corner. Two thinking creatures, only one of us a king of the forest. I’ll stick to the glaciers and we’ll be square, right?

While I was standing there, miles from snow or my RV, I pulled out that proverbial compass that had taken me through decades and miles, and wondered where I’d point it next. There are a few givens in life. Among them are these: Happiness is made, life’s speedometer has no governor and adventure is contrived. And the constant is now. You have to get out there and start walking to wherever your compass points. When I opened my fridge and cracked a beer at my RV, I found that my easy chair was the last bearing I’d take on this day. x

Jason Hummel is an outdoor adventure photographer based in Gig Harbor. He’s currently working to ski every named glacier in Washington state. Find his stories and imagery at Jasonhummelphotography.com.